Glider 26 carried a surgical team in the invasion of Sicily. According to contemporary reports, the medics not only saved lives, but they also fought to do so.

Glider: CG4-A Waco 26, serial no. 243811.

Glider carrying: Surgical team of 181 Air Landing Field Ambulance.

Troops’ objective: Set up an Advance Dressing Station near the Ponte Grande bridge.

Medical abbreviations:

ADMS – Assistant Director Medical Services

ADS – Advance Dressing Station

CCP – Company / Casualty Collecting Post

RAP – Regimental Aid Post

SMO – Senior Medical Officer

Manifest

Surgical Specialist )

2 Op Rm Assts. ) Surgical Team

2 Nursing Orderlies )

1 General Ord. )

Cpl Stretcher Bearer

2 Stretcher Bearers

Cook.

Driver Mech R.A.S.C.

2 Glider Pilots

Weight: 2,475 lbs.

1 Handcart with medical stores

Weight: 400 lbs.

Guns, Sten, Mk II 2

Magazines for 10

Total: 2,875 lbs.

Known passengers:

Capt Guy Rigby-Jones, Surgical Specialist

L/Cpl Fred J Budd, Medical Orderly

Pvt Victor N Winter

Pvt F Martin

Pvt Arnold P Jackson

Other possible passengers:

Capt J G Jones

Cpl A Buscaglia

L/Cpl M Ginsberg

In addition to the six-man surgical team and the three-man stretcher-bearer team, the passengers include, interestingly, a cook and a driver. Although a cook might not be one’s first thought for inclusion in a dressing station’s personnel, the need of those being operated on for special dietary considerations seems obvious with hindsight.

The driver was presumably included because the intention all along was to commandeer Italian ambulances. Other medical gliders contained jeeps, or “blitz buggies” as they were known at the time, which were the only vehicles that could be landed by Waco to act as ambulances, and these were accompanied by their own drivers. But they were small and in any case were lost when their gliders came down in the sea. But no Italian vehicles were used until the day after D Day (D+1). Instead the best that could be managed at first was a Sicilian donkey cart. Perhaps the medical team’s Driver Mechanic RASC was assigned to “drive” it.

USAAF Tug Pilot’s Report

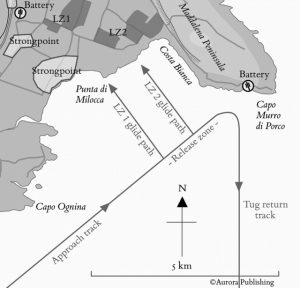

Tug: C-47 or C-53, serial 41-18418, nose (squadron) number 61, second plane of four in element 7, 12 Squadron of 60 Group of 51 Troop Carrier Wing USAAF.

Takeoff: Planned c. 18:54 from Airstrip A, El Djem Base, Tunisia. Priority 22.

Pilot 1st Lt Sidney Slotoroff:

“Hit release point. Did not vary course. Released at 2237 hrs at 1800 ft.”

“Saw some machine gun fire and light flak.”

Crew:

Co-pilot: 1st Lt Clyde W Saunders

Air Engr: Sgt Joseph A Serosky

Rad Oper: Cpl Herbert A Rhoads

Slotoroff’s after-action report, even by the terse standards of the night, was one of the briefest. As with any aircrew debriefing after an eight hour night combat flight, the men would have been exhausted, and being marched in to talk to the intelligence officers immediately after landing was probably not on their wish-list.

Slotoroff‘s aircraft, number 61, crashed and burned four days later while full of British paratroopers during Operation Fustian, the assault on the Primosole Bridge. It had presumably been hit by enemy, or, sadly, friendly AA fire. The bodies were so badly burned that many could not be identified. The US crew must have died along with their British charges. This was not, unfortunately, an isolated case, and the fact that many US pilots died flying through point-blank AA fire during Operation Fustian stands against charges of cowardice levelled against them by some after Operation Ladbroke.

Glider Pilots’ Report

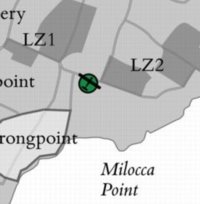

Glider allotted Landing Zone: LZ 1.

Glider Pilots: S/Sgt Walter Naismith & Sgt Coppack:

“Considering weather, good tow. Glider was cast off early by tug at 2230 hrs at 2000 ft and approx. 3000 yds off shore. Glider made successful landing approx. 1/4 mile short of L.Z.”

According to plans, the glider was supposed to be released at about 22:22, so it’s not clear at first what “cast off early” means, as 22:30 is later, and Slotoroff, the tug pilot, reported the release as even later, at 22:37. Also both the height and distance from shore were in line with plans. So it seems that the GPs meant that they had been unilaterally released by the tug without their agreement. The fact that this happened at all to quite a few gliders has been the source of much controversy over the years. However the glider made one of the best landings of the night, in terms of closeness to the LZs, so clearly the tug pilots made the right choice.

Landing

Glider 26 landed in a flat, open, stubble field only 250 yards from the south-west corner of LZ 2. It made one of the most accurate landings in the brigade, only 400 yards from the edge of its target LZ, LZ 1. It broke its right wing when it hit a tree and lost its wheels on touching down, but it landed successfully only feet away from the outbuilding of a farm. The nose, despite being seriously damaged by the landing, was raised to remove the handcart.

1st pilot Walter Naismith (who died in 2011) was later recorded in a video interview. In it he describes, wryly, how hard it was in the darkness to know how low they were, until his second pilot reported that they had just flown past a tree. Suddenly another tree appeared right in front of them. Naismith tried to pull up, hit the tree, and then “mushroomed / pancaked through the branches” into the ground. He chuckled at the memory of his relief that everybody survived this scrape unhurt.

A inspection report at the time gave more details:

Struck trees while making its landing approach and apparently stalled onto the ground. The glider ground-looped 90 degrees. The force of the landing buckled both lift struts, washed off both landing gears. The wooden structure on the nose section was completely disintegrated”.

Glider 126 landed only 100 yards away.

There was a large pillbox behind barbed wire about 500 yards to the south of Glider 26, but otherwise there seem to have been no enemy in the vicinity.

Actions

Unlike many of the gliders, there is quite a lot of detail available for the story of Glider 26. The key sources are reports by Col Eagger (the ADMS of 1 Airborne Div) and Lt Col Warrack (the SMO of 1 Air Landing Brigade), and medal citations for Rigby-Jones and Winter, written at the time. There are also books by Howard Cole and Niall Cherry, who gathered personal reminiscences after the war (see below for more information). Reports and reminiscences of course are rarely complete, crystal clear or even in agreement, so there are still uncertainties in the tale.

After landing, the party under Rigby-Jones took their handcart and headed north towards the farm building that had been chosen as the place where they would set up their ADS. It was near the main road and not far from the Ponte Grande bridge, so it was well placed to handle casualties from either the bridge ahead or the LZs behind.

Here Rigby-Jones found that the farm was only 300 yards from a still-functioning Italian roadblock and strongpoint, which was codenamed Walsall. Walsall featured a pillbox and a tall tower (in fact an inland lighthouse) surrounded by barbed wire. The tower was armed with machine guns and had clear views of the farm from across a shallow valley. The medical team dug in and waited. Gradually fighting troops of the glider brigade caught up. These men launched an unsuccessful attack on Walsall, and then decided, just before dawn, to go round the strongpoint and head on to the Ponte Grande bridge. They left their wounded with the medical team.

Although the farm had been chosen as the site for an ADS, where surgical operations could be performed, it seems that due to damaged and missing equipment it never progressed much beyond acting as a RAP, administering first aid. And at first, even before that, it was merely used as a CCP, where wounded men were gathered to await help. By dawn the medical men were in the farm and wounded were coming in, but Warrack’s report says that it did not open as an ADS until 6pm, well after Walsall had fallen and the area was secure.

Before that, however, the farm came under attack from Italian troops. Different sources give different times for this attack, ranging from morning to afternoon. It could have come from a variety of sources. Walsall and the area around it were defended by the 1 Company of the Italian 385 Coastal Battalion, with support from an additional machine-gun unit. During the night and early morning various fighting patrols and other detachments from 1/385 were sent out to clear the area of glider troops. Later in the morning, Italian regular (not coastal) troops and reinforcements poured into the area from the north. Then, in the afternoon, Italian coastal troops from further south were forced back through the area by British seaborne troops.

The British walking (and even crawling) wounded at the farm had been deployed in its defence, and the influx of Italians led to a battle. Despite officially being non-combatants (see below), the medical team fought, helping in the defence using their pistols and captured weapons. The following excerpts from medal citations for two of the Field Ambulance men give a flavour of the action:

Guy Rigby-Jones (Military Cross):

“this medical detachment, now increased by four combatant soldiers, was waiting in a farm when it was attacked by about 30 Italians … Captain Rigby-Jones decided to counterattack and himself gave covering fire to a party moving round from a flank before he joined in the assault. The enemy were driven off leaving several dead and wounded and 12 prisoners in our hands.”

Victor Winter (Military Medal):

“in the counter attack which followed this soldier volunteered to take his place in the assault party which was to attack the enemy. Armed with a captured enemy carbine and a knife, Private Winter was in the forefront of the attack.”

It seems the medical team took lives, but they also probably saved many, including enemy, both at the farm and later in a hospital in Syracuse. At the farm they treated about 50 soldiers: 24 airborne, 5 seaborne and 20 Italian. In Syracuse they worked for 10 hours, performing 22 operations.

The SMO’s Report

Part of Warrack’s report follows, and gives an overview of 181 FA’s actions:

“6 gliders became safely airborne by 1900 hours on 9 July & proceeded to SICILY – the journey was very bumpy. All gliders were cast off within a radius of 10 miles from the coast. One was close enough to make a safe landing – the remainder landed in the sea.

The glider which landed safely was that containing the surgical team under Captain Rigby-Jones. He proceeded with his party to the pre-selected area and eventually, after a small battle with the enemy, succeeded in establishing a small Dressing Station and dealt with over 30 casualties. This was in the farm at 127295 [a typo – actually 127285] and was open for about 20 hours until 14:00 hours on D + 1.

Transport in the shape of an ass-cart was procured and Captain Rigby-Jones collected in a number of patients. These were treated and evacuated to 141 Field Ambulance in transport procured by A.D.M.S. Airborne Division from A.D.M.S. 5 Div. The surgical team opened up and operated in the M.D.S. 141 Field Ambulance in SYRACUSE from D + 1 – D + 2.

…

Civilian ambulances were procured and used for the collection of casualties on D + 1 and D + 2 by A.D.M.S. and S.M.O. By the end of D + 2 it was reckoned that all casualties had been cleared into the seaborne Medical Service.

On D + 3 day, the airlanding medical services left the island. 2 officers and 12 O.Rs. of the Field Ambulance embarked.

Casualties sustained by the Field Ambulance –

Killed – Nil and 2

Wounded – Nil and 6

Missing – Captain Greeves and 15 O.Rs.

Types of Casualties –

It is thought that about 50% of the casualties found were the result of glider crashes – these mostly involved wounds of the lower limbs. “

Non-Combatants?

It is unusual to hear of medical men engaging in combat. They were accorded special protections under the Geneva Convention, and these depended on not violating their non-combatant status. This fact was carefully pointed out in operation orders, which also mentioned that breaching the rules jeopardised the lives of everybody in the medical services.

Nevertheless most sources mention the medical men fighting for the farm. There seems to have been little concern about the fact that the medics fought. In fact, Warrack’s report recommended:

“It is considered essential to arm each RAMC glider party with offensive weapons as well as with pistols.”

In his report, Eagger strongly disagreed. He pointed out that there was no evidence that any British medics had been knowingly and deliberately attacked. He was probably right. The farm was out of sight behind an orchard and trees, down a long drive away from the road. Also, there were fighting men without Red Cross armbands who were outside and would have been the first to be encountered by the Italians. There is no mention of the farm flying a Red Cross flag.

Finally there is the report by Lt Col Walch, one of the founders of the British airborne forces alongside his boss, Major General ‘Boy’ Browning. Browning had been assigned as airborne advisor to the Commander in Chief, General Eisenhower, and Walch went with him. Despite his senior HQ status, Walch managed to get a plane and glider to take him on Operation Ladbroke, but in a strictly observer capacity. Nevertheless, Walch reached the Ponte Grande, passing the RAP / ADS as he did so, and became senior officer at the bridge during the battle. He was full of admiration for the initiative shown by the glider men, but noted that their action was unorthodox:

“Another (somewhat irregular) instance of resource was that of a surgical team who carried out a spirited attack with pistols before getting their own role organised.”

The Landing Site Today

Until only a few years ago the scene of Glider 26’s landing was almost unchanged since the time of Operation Ladbroke. Now extensive building of new houses and roads, plus new farming techniques, has changed the look dramatically. The farm is still there, but whenever I have passed the field it has usually been covered with plastic tunnels instead of stubble (the farm is private and did not welcome my curiosity when I knocked). The pillbox is still there, and an electricity substation in a small tower that was present in 1943 completes the picture.

(Observations accurate at the time they were made, although things may since have changed).

Books

Books about the British airborne medical services in WW2 (still available at the time of writing):

- Niall Cherry, “Red Berets and Red Crosses”, second edition 1999, Sigmond Publishing. This can be ordered directly from the author: arnhemdescent@gmail.com

- Howard Cole, “On Wings of Healing“, 1962, reprinted 2009, Naval & Military Press

For other in-depth stories about individual gliders in Operation Ladbroke, click here.

Great account of my great uncle’s part in Operation Ladbroke – thank you

It’s a pleasure, John. Glad you like it. And thanks very much for your feedback. As a result, I’ve updated the article.

I have updated this article again, following further research and analysis of the sources.

I was really interested in this article as my Dad, Arnold Jackson, was a young male nurse with this team. He has never spoken a great deal about his experiences, neither in Sicily nor in Arnhem, though he has always answered my questions. He is still fairly active – now 96.

Thanks very much Raeyada. I have a record of a Private A P Jackson, Army Number 14275901, as being attached to the HQ of 181 Field Ambulance, i.e. with Rigby-Jones. That must be your father – I’ve added him to the record above.

Thank you – yes, that’s my father. He was with Rigby-Jones in Sicily and Arnhem and was one of the last people to be sent home from Arnhem – have you done anything on Arnhem or is Sicily your main area of interest?

The website is a spin-off from research for my book, which is about Operation Ladbroke, but there are also some articles about other airborne operations including D-Day, Varsity, Crete and Eben Emael. To date, however, nothing about Arnhem.

Hi my name is Niall Cherry the author of the book on the medical services in the 1st Airborne Division as mentioned above…the email address to contact me is now arnhemdescent@gmail.com The book has now been reprinted 5 times and the last one was a couple of years ago will be the last one and I have about 40 copies left and once they are gone they are gone!

Thanks Niall. I have updated the email address at the bottom of the article.

My Dad PVT F Martin received a broken nose while landing according to the book “On the wings of healing.He couldn’t swim and said he was lucky to reach land in that assault where so many drowned.

Thanks for your comment. Yes, the landing was a rough one – a stall into the ground followed by a 90 degree twist, so injuries like broken noses were inevitable, as the seat belts in the Waco were waist only. This left the faces of the men in danger of slamming forwards onto anything in the way, such as the handcart, which was carried between the two rows of seats.

Hi all. I’m Ex Commando and AB myself. My grandad serviced with 181. He is in one of para pictures on the para web site. Private G Smith 7382377. Was on Op Ladbroke and Arnhem. POW in Stalag 12B I gather. Contact me in Simon.smith121@yahoo.co.uk. If any details. Looking to retrace his steps for the 75th in sept 2019.

Hi all. I’m Ex Commando and AB myself. My grandad serviced with 181. He is in one of para pictures on the para web site. Private G Smith 7382377. Was on Op Ladbroke and Arnhem. POW in Stalag 12B I gather. Contact me in Simon.smith121@yahoo.co.uk. If any details. Looking to retrace his steps for the 75th in sept 2019.

Thanks Simon. Your grandad was with Section 2, headed for LZ1 with the South Staffords. It was carried in 3 Wacos – 22, 26 and 30. If he landed on land, then he was in 26 (see article above). If he landed in the sea, then he was in 22, as he is not listed as being in 30. There is no list for Waco 22, which carried a jeep crewed by a CO and three ORs. It came down “far out to sea” after being forcibly released by the tug [story]. For more information about the 181 Field Ambulance gliders that landed in the sea, see [here]

Thanks Ian. Very helpful!