The pilots of Glider 124 staked everything on reaching land. A few inches of height either way meant the difference between life and death.

Glider: Waco 124, serial no. 277233.

Glider carrying: Half of 14 Platoon, B Company, 1st Battalion of the Border Regiment.

Troops’ objective: Outskirts of Syracuse.

Manifest

1 sjt

8 men

2 men R coy

1 Sig Bn HQ

1 Handcart

Sjt Gorbell, Howard

Pvt Boardman, E

Pvt Caldwell, Douglas Henry

Pvt Collins, Ronald

Pvt Fitzpatrick, Nicholas

Pvt Fraser, Gordon Anderson

Pvt Sanderson, G

Pvt Simmons, Frederick

Pvt Tomlinson, John William

Pvt West, Lionel Arthur

Cpl Willoughby, Joe

Pvt Wood, William

Glider pilots:

First pilot: Staff Sergeant Iron, Hedley James

Second pilot: Sergeant Nelson, Geoffrey Edward

The four rifle companies (A to D) were topped up for the duration of Operation Ladbroke with men from R (Reserve) Company (formerly T Company, the Training Company). In this case only 2 men from R company were on board. They were Wood and Simmons.

The signaller, West, was from Battalion HQ, and not known to the men of 14 Platoon:

“Just as we were leaving, someone asked if we had any room & a signaller was pushed into the glider as we had one empty seat”

All three of these last-minute additions died.

B Company was spread across 13 gliders. Only 3 of the 13 gliders landed at all in Sicily. Most landed in the sea [story].

Apart from the gliders carrying B Company’s platoons (11 to 14), others carried mortar teams and Company HQ. Half the platoon gliders carried handcarts, which were pulled by two men. These carried heavy equipment, such as radios. They also carried other essentials such as extra ammunition, as the ability to hold out when surrounded behind enemy lines was a key requirement of airborne warfare.

Tug Pilot’s Report

Tug: Albemarle [photo], letter Z, number P1525, 296 Squadron, 38 Wing RAF.

Takeoff: 2002 hrs (8 mins late), Airstrip F, Goubrine No. 1, Tunisia. Priority 14.

Tug return: 0240 hrs (1 hour 21.5 mins late).

Pilot: Sqn/Ldr D I McMonnies, with Sgt C N Greenhead, F/S K Blackhurst, W/O J Smith

The debriefing summary by 296 Squadron RAF reads:

“Tug pilot reported release was late but believed to be at correct height and position.

(Statement by passenger):

Glider hit cliff and fell back into sea. Severe crash into sea. 3 wounded, 9 missing, believed drowned.”

The time the glider was released was recorded as 23:52, well over an hour late.

Statements from passengers were usually only gathered when both glider pilots were dead.

In this case it seems the passenger was wrong, as, based on other information (see below), it appears that the glider came to rest on the rocks below the cliffs, and the ten ‘missing’ men died in the crash, not from drowning.

McMonnies was an extremely experienced pilot, having been one of the first pilots to work with airborne forces, at the Central Landing School in June 1940. No explanation is given as to why the glider release was so late. RAF crews were used to night operations and each had an experienced navigator. Yet McMonnies’ navigator would have to have gone seriously astray to account for such a delay. As things turned out, McMonnies was not just late but also in the wrong position, as the glider crashed over 6 miles away from its intended LZ (LZ 2). As for the height of the release, it’s possible it was technically correct, but in the end it wasn’t enough, by the slimmest of margins.

The Crash

Sergeant Gorbell was the senior NCO in 14 Platoon. He later described what happened:

“On the night of 9th July 1943 I was the Senior passenger of the above Glider, engaged in the operation of the invasion of Sicily. On approaching the coast of Syracuse, which was our releasing area, we met a considerable amount of ACK ACK fire. We were released just as we approached the cliffs, I had given orders for bayonets to be fixed, when I noticed the nose of the Glider down, to come into the landing lane, which could be seen below, the only other thing I remember was hearing Pte. Boardman who was one of my platoon shouting is anyone alive, he helped to pull me out from under the Handcart under which I was pinned. On inspecting the Glider I discovered it had crashed head on into the face of a Cliff.

I personally inspected the crew of my Glider, all personnel as mentioned were Dead.

The men were last seen as follows: The Glider in which we were travelling was embedded into the ground, the bodies of the first four men was inside the ground, the remainder of the crew were all heaped on top of each other, except three of us which were separated from the remainder by a spare ammunition cart, which I think we owe our lives to. We were lying for thirteen hours before being picked up during which time there wasn’t a sound from any of the remainder. I personally inspected them three times during daylight. I assumed they were beyond aid. “

After hitting the top of the cliff, Glider 124 fell the entire height of the cliff onto the rocks below. Besides Gorbell and Boardman, the only other survivor was Sanderson. All three men were wounded. Eleven men, including the glider pilots, died in the crash. Given the circumstances, it’s a wonder that anybody survived.

It’s possible the glider pilot could not see the cliffs in the dark. Even if he could see them, he may have felt that he could reach land, as he did not turn away and land in the sea instead. He would have to have done this in enough time to complete the turn and level up before splashing down. Once he was past that point, he was committed. He may have tried to climb at the last minute, without enough speed to clear the top.

Typically the first pilot flew the glider while the second pilot called out the height, which he read from the altimeter. Unfortunately many altimeters that night were giving readings 100 to 300 feet higher than the glider’s actual height. This may have happened here, and tipped the pilot’s decision to try to land. He almost made it, as the glider hit the top of the cliff only a few feet below the top. But that small margin was fatal.

The pilots and their passengers were unlucky. Other gliders in the same predicament were luckier. The pilot of Glider 105 only saw the cliff in front of him when a searchlight switched on and revealed it. He swung the glider up and it stalled onto the cliff’s edge. Glider 10, piloted by Staff Sergeant Andy Andrews, also touched down on the top of a cliff, narrowly escaping crashing into it. The men in Glider 10 went on to be heroes of the day, storming an Italian gun battery on their own initiative. Andrews went on to become a senior figure in the Glider Pilot Regiment, and a key player in the glider assault on Pegasus Bridge, which spearheaded D-Day in Normandy less than a year later [story].

There are a couple of anomalies in Gorbell’s account. He says he ordered his men to fix bayonets, but doing this before the glider rolled to a stop was specifically forbidden in 1 Border’s orders for the night, in case men were injured by bayonets in a rough landing. Also, Gorbell mentions seeing a landing lane. The fields behind Capo Negro, where the glider crashed, were narrow and arrayed perpendicular to the coast, so they indeed may have looked like landing lanes in the moonlight. And yes, the gliders were expected to land in adjacent lanes. Absurdly, given that only a handful reached the LZs at all, they were supposed to end up nose to tail in orderly lines. But there were no lanes marked on the actual LZ. Perhaps lanes had been marked during rehearsals, and Gorbell somehow expected to see the same in Sicily.

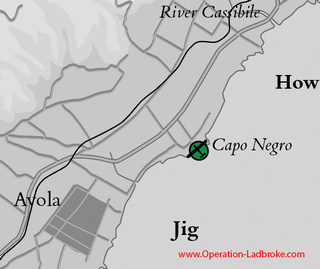

Glider 124 crashed in a bay adjacent to the west side of Capo Negro, near Avola [map].

Aftermath

D J Lewis was a Canadian sailor who served with a flotilla of landing craft off the How and Jig beaches in the British sector of the invasion. He took a photograph of Glider 124 pancaked at the bottom of the cliff. Many years later he wrote that the experience remained ‘uncomfortably vivid’, in particular the ‘dreadful smell’ emanating from the dead bodies in the glider. In the clear waters offshore he recalled seeing dead glider troops from other ditched gliders floating ‘like mermen’ in the depths. He described how they eventually floated to the surface and were then towed ashore for burial. Lewis’ account and his photograph appear in the book ‘St. Nazaire to Singapore: The Canadian Amphibious War 1941-1945’, on page 181. You can see it online [here].

Ten bodies from Glider 124 were collected and buried by 32 Brick (a ‘brick’ was the name for a Beach Group, comprising a Beach Master and a detachment of men whose job it was to control the landings on their beach). They reported that the bodies were unidentified. This meant the men in the glider could only be listed as missing, especially as there was also a discrepancy in numbers. As was usual with missing men, an investigation was launched, in case any of them had survived the crash, and was a prisoner of war, or was lying in a hospital somewhere, seriously injured.

It’s a truism that it’s easier to be touched by the story of a single death than by statistics of many deaths, or by lists of many dead, even though in theory the greater number represents the greater tragedy. British investigations into the missing tend to be moving by focusing on individuals. Both Gorbell and Sanderson were interviewed in hospitals in England. It is easy to imagine them in their hospital beds, remembering their platoon mates for the benefit of the ‘searcher’ (as they were called). One of the missing was “small, very boyish looking, mousey coloured hair”. Another was “an inveterate pipe smoker” from Lancashire. Another was “5ft 9ins, very boyish, fresh complexion, blue eyes”. More poignantly, in the words of one searcher’s report:

“With regard to Tomlinson 3598428, Informant has a book for Mrs Tomlinson on the flyleaf of which the dead man had written a letter to his wife. He would like Mrs Tomlinson’s address.”

The missing men were never found alive, of course, and they are listed on the Cassino Memorial to the missing of the Italian campaign. Nor were their bodies ever identified. If the bodies were found, then they would probably have been transferred to the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Syracuse. Here they would now lie under anonymous tombstones, unknown to us, but, in Kipling’s resonant phrase, ‘known unto God’.

.

A clearer copy of D J Lewis’ account and photograph can be found on Gord Harrison’s Canadian Combined Operations website [here].

Thank you, you have put to rest the rumours and half truths that have surrounded the death of my fathers cousin for many years. Private Gordon Anderson Fraser. My father and Gordons sister Alexandria who are no longer with us held a mis-guided grudge against the Americans upon receiving the tragic news of Gordons passing. All they had was an old local paper cutting of the time mentioning Gordon and the tragic event that took place.

Thanks Brian. So pleased to have been helpful.