The pilots in Glider 110 landed their Waco in the centre of LZ 1, then went on to fight to the finish for the Ponte Grande bridge.

Glider: Waco CG-4A number 110, serial no. 73603 (or 73683).

Glider carrying: 6 pounder anti-tank gun and crew of H Company, 1st Battalion of the Border Regiment, 1st Air Landing Brigade.

Troops’ objective: Anti-tank defence of the outskirts of Syracuse.

Manifest

1 sjt

2 men

1 – 6-pdr

According to glider pilot Boucher-Giles the gun crew included:

Sgt Hodge.

A corporal he identified only by the name ‘Paddy’.

Glider 110 was one of four H Company gliders (109, 110, 117, 118) that each carried a 6 pounder anti-tank gun. The guns were too heavy to manhandle far, so another four gliders (114, 113, 121, 122) carried specially adapted jeeps (known at the time as “Blitz Buggies”) to tow the guns. The Waco glider, unlike the Horsa glider, was not big enough to carry both a gun and its jeep. Of the eight gliders, two had to abort shortly after take-off, and another three came down in the sea off Sicily. Two which carried guns landed in Sicily, as did one glider which carried a jeep, but it landed many miles away. The result was that none of the eight H Company gliders fulfilled its purpose. The idea that the jeeps would easily find their guns in the dark, in countryside full of trees and stone walls, when the gliders were likely to be so widely scattered, proved to be one of the most over-optimistic parts of the plan for Operation Ladbroke.

Tug Pilot’s Report

Tug: Albemarle Mk I [photo], letter K, number P1389, 296 Squadron, 38 Wing RAF.

Takeoff: 1942 hrs 9 July 1943, Airstrip F, Goubrine No. 1, Tunisia. Priority 16.

Tug return: 0055 hrs (16.5 mins early) 10 July 1943.

Pilot: Sqn/Ldr L C Bartram, with P/O C A C H Foster & P/O J G Walters

“Glider released at 1400 ft. 1000 yds off coast on release line. Glider landed approx 300 yds N. LZ 1. Glider broke on landing but one passenger injured when gun broke loose, otherwise O.K. Glider caught in searchlight after release but S/L lost glider after approx. 800 ft.”

First Glider Pilot Boucher-Giles later reported:

“I learned afterwards that our tug had followed us in to protect us, and had shot out the searchlight.”

If this is correct, it seems odd that the tug pilot did not mention it.

Glider Pilot’s Report

Two sketches in glider pilot Victor Miller's notebook. The left sketch showing a Waco in the air on tow is captioned "Sousse 7:15pm BEFORE". The right sketch showing his smashed Waco on the ground is captioned "Syracusa 10:15pm AFTER". Compared to his other drawing of his landed glider (top), the damage seems exaggerated, but Miller was clearly making a point.

Glider allotted Landing Zone: LZ 2.

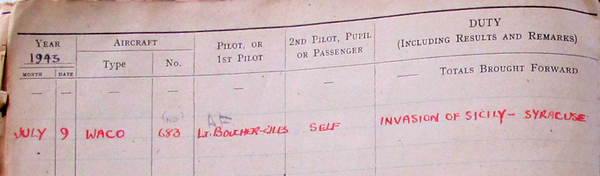

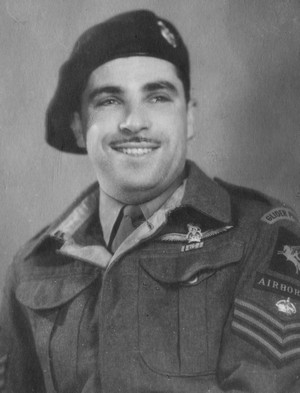

First Glider Pilot: Lt Boucher-Giles, Arthur Francis

Second Glider Pilot: Sgt Miller, Victor

“A first-rate tow and good navigation, but inter-comm. went u/s. Glider released at 2240 hrs at 1400 ft. approximately 1200 yards off coast and made successful landing on L.Z. One man injured in landing by gun load breaking loose.”

“Glider Pilot’s suggestions:- Intercomm. u/s suggests intercom in glider be lashed at convenient point. Consider 6 pounder gun and 3 men too heavy a load. Strong points not strong enough in bumpy weather. Suggest Sutton harness for 1st and 2nd. pilots.”

The landing may have been successful and almost exactly in the centre of an LZ, but it was the wrong LZ. Glider 110 landed in LZ 1, when it was supposed to have landed in LZ 2.

Ten years later Boucher-Giles wrote an account of his part in Operation Ladbroke in an article for The Eagle, the magazine of the Glider Pilot Regiment Association. It explains how he came to end up on the wrong LZ:

“I looked out of the port cockpit window and the sight that met my eyes from the L.Z. 2,000 ft. beneath and in front of us seemed far from healthy. At least three gliders were on fire on the ground and burning fiercely, while the criss-cross of many tracer bullets indicated a battle going on below us. To use an R.A.F. expression which is, for all I know, still current in the service, there seemed no future in all this, so we simply took off the lift spoilers again and glided on over the L.Z. to land in a field about a mile further on, as we thought, in safety. But a searchlight got us at 1,200 ft., plus a small amount of light flak, so that after the excitement of weaving to escape it, and the dazzling light of the searchlight, we had to make a quick and, I fear, rather heavy landing. We came to rest with a heavy crump in a cloud of dust.”

Later examination of the glider showed:

“Landed on smooth sod field at terrific speed causing the floor to almost completely disintegrate. Stopped 120 feet from where it first contacted ground. There were two deep holes where the wheels first made contact. It was apparent that the pilot was travelling at a terrific speed and did not level off sufficiently for landing.”

The author of a second report was somewhat more scathing:

“Perfect field […] absolutely no reason for extent of damage but improper landing.”

The Second Pilot, Victor Miller, has left us a full account in his book, ‘Nothing Is Impossible‘. It explains how the landing came to be so hard. After handing over control of the glider over to Boucher-Giles (BG), Miller watched the instruments and called out the readings:

“I chanted the airspeed of 100 mph and a height of 600 feet through the dull roar that filled the cockpit. I had to lean right forward to take the readings, for the figures on the altimeter were very indistinct. Still, we sailed on down through the night to our landing zone, undisturbed now by flak or searchlights. Again I shouted out the figures to BG, 100 mph, 400 feet. […] Dead ahead appeared a faint white outline that indicated an open space. On each side and on the far end, dark masses indicated trees, and these we would have to avoid at all costs […] I knew at 100 mph we were gliding a little fast by about 10 mph, but undoubtedly BG was trying to get down on the dim white spot. Once more I called out a reading of 100 mph, 200 feet. It was the last thing I remembered for a while, for the next second there came an exploding crash.”

Miller was knocked out when his head hit the dashboard, which is presumably why Boucher-Giles suggested fitting Sutton Harnesses instead of the standard Waco seat belt. Both pilots’ night-vision was ruined by the searchlight, causing Boucher-Giles to rely too much on the instrument readings, while simultaneously making it hard for Miller to read them, even when peering closely at them. Unfortunately the altimeter was reading too high. There were several reports that night of altimeters misleading pilots into hitting the ground while still descending rapidly, as happened here.

The hard landing was compounded by the heavy anti-tank gun breaking free and apparently smashing through the floor, also injuring the gun crew’s sergeant.

Boucher-Giles may have thought poorly of his own performance, but those in authority obviously disagreed with him. He was one of only three glider pilots to be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for Operation Ladbroke.

Defence of the Ponte Grande

We are unusually spoiled when it comes to accounts of Glider 110. We have Boucher-Giles’ 1953 account in The Eagle, and versions of it in later books. We also have Miller’s very full account in his book ‘Nothing is Impossible’. Few other Operation Ladbroke gliders are as richly documented with detailed first-person accounts.

Glider 110 came under fire immediately after landing, but the firing soon stopped. One of the gun crew was left behind to look after the injured sergeant, while the other (‘Paddy’) accompanied the pilots. They worked their way cautiously northwards, moving from field to field. They hid behind a wall while the RAF raided Syracuse, dropping flares that turned the night to day. They met a group of glider troops, some wounded. These men had no officer, so Boucher-Giles took command. More stragglers joined as they moved on.

Eventually they arrived near the regimental aid post (RAP) that had been set up on the ridge south of the Ponte Grande bridge by the airborne medics. They left the wounded there. The RAP was close to an Italian strongpoint, codenamed Walsall, which dominated the approach to the bridge. The glider troops launched an attack on the tower at the centre of the strongpoint, but they failed to take it. They decided to go round it instead. Dawn was breaking as they crossed the open ground between Walsall and the bridge, coming under machine gun fire from a gun battery codenamed Gnat.

They found the bridge in airborne hands, with the demolition charges neutralised. Boucher-Giles estimated that eventually there were 65 glider men defending the bridge under the command of Lt Col Walch (although Walch’s estimate was 87). They spread out to defend all four quadrants, but there were not enough of them, and they had almost no heavy weapons and limited ammunition.

Casualties began to mount as they came under attack by a large number of Italian troops supported by mortars and a field gun. Boucher-Giles described the increasingly desperate plight of the defenders:

“A shell burst in the water in the midst of a group of Staffords and caused a sight I try to forget. Sniper bullets were finding their mark, and so were the constant mortar-bombs. The trouble was that soon the casualties were too great to allow us to guard every possible approach to the bridge, and the enemy began to enfilade us. […]

[Our men] were all magnificent. Sixteen glider pilots and some four or five others joined me on the south bank of the southernmost canal, Lts. BARCLAY, DALE and HALSALL, S/Sgts. MILLER, CAWOOD […] and BARNSDALL [Barnwell], others whose names escape me, and right to the last, the redoubtable “PADDY” […]

We held on for the best part of an hour after the remnants of the party on the northern bank had been all killed, wounded or taken.

A sniper knocked a tin of tea out of my hand. The second-in-command [Major Beazley] swam the canal to us, to be greeted by a burst of machine-gun fire which killed him and one of my best sergeants [S/Sgt Wikner], and favoured me with two bullets in my pack, a flick across the cheek by another bullet, and a direct hit on my rifle.

Half of us were in the canal now, for better cover just under the bank, and we toppled over one or two bolder spirits when they broke cover at last to throw hand grenades at us.

Then we took cover in a dry ditch and fought till the ammunition ran out. We still accounted for any Italian who came too near, but there was by now more than one machine gun enfilading us, the nearest some 40 yds. away.”

Boucher-Giles was concussed by an exploding grenade before he and the remaining men surrendered. They were led away, but turned the tables on their Italian captors when they encountered a patrol from the Northants Regiment. In their absence the bridge was captured by men of the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Miller meanwhile had been ordered before the surrender to go to a position on the ridge overlooking the bridge. Here, in the ruins of an ancient Greek Temple to Zeus, he and the men with him were surrounded, and he was wounded in the thigh by a grenade. Miller leaned out from cover to wave a white towel in surrender, when he saw an Italian rifleman fire point-blank at his head. The shot only grazed Miller but, terror-stricken, he was convinced he was about to be killed. He stumbled away, pursued by a flurry of shots, until he was felled by another grenade and taken prisoner. He was taken to an Italian hospital in Syracuse. British troops entered Syracuse that night and completed the occupation of the town in the morning, taking over the hospital.

Miller was then taken by ship to a British hospital in Tripoli in Libya. Here he at first found it impossible to sleep, as the nightmare memories of his nearly dying welled up in the darkness, and convulsed him with sweat and trembling.

Operation Ladbroke was Miller’s first time in action. He went on to fly gliders into combat again both at Arnhem and across the Rhine, but it was Sicily that dispelled any illusions he had about war. Before the attack on the Walsall strongpoint, he said he had felt a “peculiar attraction” to the idea. However, “once sampled,” he wrote dryly, “I found there was nothing attractive at all about attacking an enemy pillbox.”

The epic stand at the Ponte Grande by the men of 1st Air Landing Brigade may have finally resulted in victory, but it came at a great cost, even to those who survived.

Victor Miller’s book, ‘Nothing is Impossible’, can be bought from the publisher [here].

With thanks to Chris Miller for permission to quote from ‘Nothing is Impossible’, and to use his father’s portrait and sketches.

Thanks also to Pen & Sword Books for supplying the opening image.

Excerpts from Boucher-Giles’ account by kind permission of the editor of The Eagle, the magazine of the Glider Pilot Regiment Association.

A version of Boucher-Giles’ account can be found in George Chatterton’s book ‘The Wings of Pegasus‘ (1962).

[Account by Sapper Harry Stokes of 9 Field Company RE]

SICILY WAS NOT ALL FAILURE

In 1940, after Dunkirk, Major Houghton, Officer Commanding 9th Field Company, decided that we should train to fight as infantry as well as being sappers. Forty-mile route marches every Wednesday in full battle order, bayonet fighting and a general toughening up became part of our training/routine.

We moved to Wiveliscombe and it was there that we were told we were to become glider-borne troops. Major Kite took over as Officer in Command with Captain Beazley as Second in Command. I was Captain Beazley’s driver and we spent much time travelling the country looking for equipment suitable to be carried in gliders, such as trailers, compressors and the like.

We moved to Bighton, and later to Bulford. Practice gliding started from Netheravon in Hotspurs towed by small twin-wing planes. Major Kite left and Captain Beazley was made Officer Commanding.

We then moved to Africa. When the Sicily job came up Major Beazley, myself and a radio operator were allotted to a WACO glider carrying a motorcycle and sidecar, a compressor for removing charges from the bridge and pilots Lt Dale and Sgt. Baker.

We took off from Tiersville aerodrome. It was a terrible trip. All of us, including the pilots, were violently ill. The motorcycle came loose from its moorings but nobody worried because we felt so unwell. There was lots of flack and tracers but we made it to the Dropping Zone.

I remembered that at the briefing we were told to look for a house with a large “Y” on the end of it, and there it was. We landed among a hail of small arms fire. We tried to raise the nose of the glider to get the equipment out, but the firing was so concentrated that Major Beazley decided we would leave it and make our way to the bridge.

By this time it was getting light. As we crawled along ditches and hedgerows we kept being shot at. When we got near the bridge Major Beazley could see Red Berets already there. This gave us confidence and we soon made it to the bridge where the infantry were in charge. Major Beazley and I inspected the bridge and found the charges were only tied to it and covered with bundles of raffia to protect them from the weather. We were able to cut the ties and drop them into the river. Later in the morning, lorry loads of Germans arrived and a real battle took place.

During this engagement, Major Beazley was shot in the head and died immediately.

Soon after, the ten or fifteen of us left alive were taken prisoner. Later, we were being taken along the towpath when a naval picket of about 20 men overcame the guards and we were free again. Somehow — I don’t remember how – I arrived at Brigade Headquarters. I saw Colonel Henniker there and told him Major Beazley had been killed. He wanted to know the details of the bridge and if I thought it would take tanks. As a young sapper, I was a bit vague but he must have been satisfied for soon afterwards the tanks moved forward over the bridge.

I stayed on in Sicily as Colonel Henniker’s driver and he tells of our escapades in his book “Images of War”.

Harry Stokes

No. 2074228

9th Company, Royal Engineers, Airborne Division.

Thanks Peter. As you probably know, the original of Stokes’ account is in the archives of the Army Flying Museum. He wrote it and sent it to the museum as a reaction against a newspaper article he’d read headlined “Gliding Towards Disaster”, which implied Operation Ladbroke was a total failure. Hence the heading “SICILY WAS NOT ALL FAILURE”. He was of course correct. In fact it was technically not a failure at all. All of 1 Air Landing Brigade’s objectives, whether capturing strongpoints and gun batteries, or seizing bridges, or occupying part of Syracuse, served one overall objective – to facilitate the rapid capture of Syracuse by the seaborne forces. This they did, even though they failed to achieve most of the subsidiary objectives. Churchill was possibly the first person to use the word ‘disaster’ in this context, but he was referring to the extremely high casualties. Ladbroke may not have been a failure, but the cost of success was indeed high.

I’m really happy to have stumbled across this article whilst Googling today as we approach the 80th Anniversary of Operation Husky. Basil Beazley was my uncle and godfather and it’s great to have a bit more detail of the part he played as I’m now in my 80s and would like the operation to be remembered by my family. We visited the site of the bridge a few years ago it was very poignant. Thanks!

Thanks Anne. So glad you like the article. There are more mentions of your uncle [here].

Hi Anne,

Was just Googling to find some more information about Major Beazley and saw your post here saying you are a relative to the Major. I have wrote a book about the history his unit during the war and wants to write a article about the Major its self. Could you contact me at pjpronk@hotmail.com ? Thanks.