Operation Fustian or Marston? Glutton or Snowboots? Husky 2 or Mackall White? Operation Ladbroke or not? A wry look at the confusion caused by codenames.

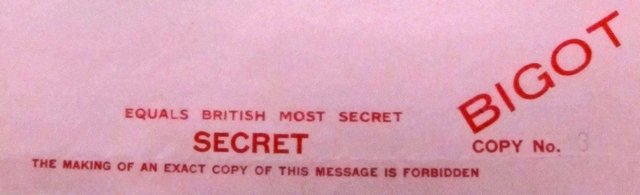

AFHQ produced Bigot messages almost by default, and had pre-printed stationery for the purpose. Confusingly, this footer of a (long since declassified) document is labelled Copy 3, despite stating that copies are forbidden.

Codenames and codewords are designed to confuse the enemy. Unfortunately, they often also confuse their own side.

In World War 2, there were codes for anything and everything that needed to be disseminated in any way, whether by phone, radio, courier or carrier pigeon. It was always possible that the enemy would somehow get hold of it. So it was vital that even if they could read the signals or documents, they would not understand them.

There were codes for places (geographical), codes for planned battles (operations), codes for when things would happen (timing), codes about the outcomes of combat, codes for military units, codes for people, codes for targets [examples], codes for ammunition and supplies. If you could name it, and the enemy would like to know it, then it usually had a codename. Codenames were primarily important, of course, during the planning phase of an operation, so that when the action began it would come as a total surprise to the enemy.

It must have been extremely difficult for central headquarters (HQ) planners to come up with endless numbers of codewords, all of which had to be unique to avoid confusion. These then had to be disseminated secretly to lower formations, who then had to keep them secret, sometimes even from people who would benefit from knowing them. Then the senders and receivers of messages that used the codewords either had to remember them all, or keep the list of secret codes handily out on their desks, when they might better have been kept locked in a safe.

In the case of the Allied invasion of the island of Sicily, our story begins with horror. The Allies had a long list of codenames for places, mainly towns but also islands and other geographical features. To the amusement of those in the know , the codename for Sicily was Horrified. Allied officers trying to discover each other’s security clearance used to ask, “Have you been Horrified?” This was a play upon the question, “Have you been classified?”, i.e. entitled to see classified information.

You might then suppose that Operation Horrified was the codename for the invasion of Sicily. If so, you might suppose wrong. It was in fact Operation Husky. Husky was the codename for the entire invasion, which began on 9 July 1943. The codename Operation Husky included all the planned actions (operations) of both the British and American armies, and all their forces, whether land, sea or air.

Was there some reason for using the codename Husky? Presumably it had nothing to do with snow and sleds. Yet the squaddies slogging up the dusty Sicilian roads in 40-degree heat probably exclaimed of the planners: “They’re having a laugh”. The brutality of the Sicilian sun clashed mightily with any thoughts of ice implied by huskies. The crushing heat was the reason that tourist guidebooks of the time strongly advised against visiting Sicily in July and August. This was another source of black humour to the men. Unlike the Baedeker travellers in peacetime, the soldiers faced death when they visited the island, so they wondered why such good advice was being ignored.

Allied airborne forces, both American and British, played vital parts in Husky. The planners envisaged multiple separate operations on separate days. You might think this would require maximum clarity and codenames to suit. Confusingly, this is not the case. For example, the American parachute drop on the first day is known as Husky 1, and its follow-up reinforcement drop is called Husky 2. Enumerating sub-operations like this was unusual. If every sub-formation did it regarding their own operations, then chaos could reign, with duplicate names in profusion. There was also the risk of confusing a sub-operation with the overall operation, yet nobody has so far renamed Husky itself to, say, Husky Zero.

It seems it came about because nobody among the central planners found the time to suggest any proper operation names. In the absence of an officially sponsored name, one planning document for what was later called Husky 1 was unhelpfully headed “Drop Zone (Horrified)”. Of course, all the parachute drops were in Horrified (Sicily), so the title does not identify the particular operation. More helpfully, the US airborne missions in Husky were also identified as “the first mission” or “the second mission” etc. From there it was presumably a short step to simplifying matters by referring to Husky 1, Husky 2. But simplicity was not a common feature of coding systems.

A complicated (and thus confusing) set of codewords was devised for signalling the details of the follow-up drops once they were decided. For example, Mackall (named after an airborne training camp in the US) called for Combat Team 2, while Bragg summoned Combat Team 3. A signal “Mackall Tonight” meant Husky 2 was a go that night. “Mackall Negative” meant it wasn’t on for that day. There were also Plans Red, White, Blue, Green, Purple and Brown for further paratroop drops. Once a plan was chosen, a silly phrase was to be combined with a colour to signify the timing of that Plan. “Carry White Hat” called for Plan White on D+1 (the day after D-Day), while “Kiss Green Lips” signified Plan Green should be executed on D+15. “Your Purple Eyes” meant Plan Purple should launch on D+7. And so on.

The document explaining some of these codes said they were intended to “speed up and simplify the procedure in launching these lifts”. They are so opaque, however, that users of the scheme may not have agreed. The enemy (if they intercepted the signals) probably felt the same – if so, job done. But you feel sorry for the Allied officer who had to code the signals. You can imagine him sweating anxiously as he checked and rechecked that he hadn’t just inadvertently called for an emergency resupply drop of coloured pencils.

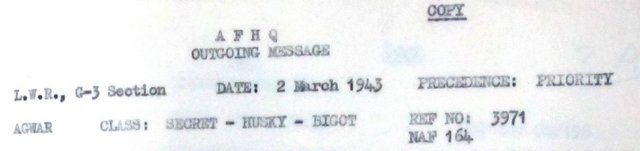

The header of a now declassified AFHQ message showing its security class as “SECRET – HUSKY – BIGOT”. Other information in the header shows it was sent by Maj Gen Rooks to the US War Department on 2 March 1943.

Husky

So why was the invasion of Sicily called Operation Husky? We don’t know. Previous plans to invade Sicily had been called Influx and Whipcord. No clues there (unless there’s a reference to the traditional whip used to mush husky teams). At one point the British War Cabinet suggested changing Husky to Bellona (the Roman goddess of war), perhaps precisely because Husky seemed strangely inappropriate. It was decided, maybe by Prime Minister Winston Churchill himself, to keep Husky. Codewords, after all, are meant to be random or, even better, misleading.

Churchill acknowledged that there were limits, however. Codenames could blow back tragically on their creators when, for example, families learned that a son, brother, father or husband had died in an operation with a patently silly name. For this reason Churchill advised against names such as Ballyhoo or Bunnyhug. Set against these, the name Bellona clearly wins hands down for having the gravitas and magnificence needed to confer glory on a military operation (compare the codename Overlord given to the invasion of Normandy a year later).

We could ask the same question of Operation Ladbroke, the glider assault on Syracuse in Sicily and the opening move of Operation Husky [story]. Did the choice of the name Ladbroke have any meaning, or was it just random, as codenames were ideally supposed to be? Ladbrokes was back then (and still is to this day) a national chain of UK bookmakers (a betting company). A year after Husky, during the invasion of Normandy in France in 1944, a series of major attacks by General Bernard Montgomery’s army were called Operations Epsom, Goodwood and Totalise. Two of these are the names of racecourses in the UK, while “the Tote” was the British state-run bookmaker.

The same General Bernard Montgomery was the man behind Operation Ladbroke in Sicily [story]. Might then these names somehow imply a heroic race to the finish? Goodwood , for example, was meant to unleash a race by the British armoured divisions, which were all set to go “swanning” (as they termed it) gloriously in the enemy’s rear. Detractors, however, would say most of these operations were indeed well named, because they turned out to be foolish gambles. Goodwood and Ladbroke in particular are deemed by many to have been massacres [story].

Operation Ladbroke was the glider assault which spearheaded Husky. Its primary aim was to facilitate the rapid capture of the port city Syracuse [map], by seizing a nearby bridge. The Allies needed Syracuse’s magnificent harbour so that supplies and reinforcements could be rushed into the beachhead. The Allied geographical code for Syracuse was Ladbroke. Hence the operation to capture the town of Ladbroke was called Operation Ladbroke.

Glutton and Fustian

The Ladbroke airborne operation was supposed to be followed by two more airborne operations to facilitate the capture of the Sicilian ports of Augusta [map] and Catania [map], also by seizing nearby bridges. The geographical codenames for these ports were Glutton and Fustian respectively. The operations were called, as you may have guessed, Operation Glutton and Operation Fustian. So far so prosaic, and it’s fairly clear that there is no pattern or meaning to the geographical codes. Other towns, for example, had geographical codes such as Appalling, Gizzard and Chimpanzee. Which rather puts paid to the Ladbroke racing and betting theory.

Operations Glutton and Fustian may have been named simply after their town codes, but little is simple when it comes to codes. Like Husky 2, Glutton and Fustian were follow-on operations, and their dates were not fixed in advance. The exact day would be decided according to events on the ground. Like Husky 2, codewords were used in signals about their timing. The Augusta (Glutton) operation’s timing code was Snowboots, while that of Catania (Fustian) was Marston.

So the signal “Marston tonight” started British paratroopers climbing into their aircraft, and set hundreds of aero engines revving on dusty desert strips. On the other hand, British paratroopers climbed back out of their aircraft when the airborne attack on Augusta was cancelled at the last minute [story]. The cancellation signal was “Snowboots not required”. Clearly, snow boots were not required in the blast furnace of a Sicilian summer. Perhaps the staff officer who dreamed up that codename was indeed having a laugh.

This double level of obfuscation (e.g. Catania becomes Fustian becomes Marston) was deliberate. It meant that the timing messages did not need to be encrypted and then decrypted. This allowed for rapid responses to tactical developments during battle, as the messages would not be seriously delayed by overworked cipher clerks. The geographical codes for the towns (such as Ladbroke and Fustian) had been in use for months, while it seems Marston and Snowboots were coined just before the invasion. This meant they were less likely to be known to the enemy, and were thus more suitable for unencrypted messages.

However, in an after-action report, a senior signals officer commented on the lack of encryption:

“‘MARSTON TONIGHT’ was sent back to Airborne Base in clear on D+3 at 1530 hrs. It is reasonable to assume the enemy had by then identified the Airborne base wave, with the result that the message probably gave warning of an event connected with airborne troops, even if the meaning of MARSTON was not known.”

The same officer called the operation Operation Marston, not Operation Fustian. In fact Marston was the codename for the Primosole bridge, the primary target for the paratroopers of Operation Fustian. Using the bridge’s codename was a reasonable choice for the unencrypted timing signals, but it led to the operation acquiring a potentially confusing second name. This confusion persists to this day.

Something similar happened with Operation Glutton. No less a person than Admiral Andrew Cunningham, Commander in Chief of the Allied Mediterranean fleet, sent a signal to all ships on D+1 containing only two words: Operation Snowboots. It was a warning to his sailors not to shoot down the low-flying paratrooper planes of Operation Glutton as they passed overhead. In the end, the operation was cancelled, but only at the very last minute. Ironically, it seems the message was delayed because it got unnecessarily encrypted by mistake.

Also ironic, if tragic, is the fact that when the planes of Operation Fustian flew over the Allied ships two days later, many were shot down by their own side, despite the fleets having been warned. If the fears of the senior signals officer quoted above were correct, then the warning signal may have inadvertently alerted the Germans that the paras were coming. But it seems it failed to fully alert the Allied forces. There was not enough time to disseminate the warning to all the anti-aircraft gunners on all the ships, thus contributing to the friendly fire disaster. Leaving coded timing messages to the last moment was not without its perils.

Although the use of the codewords Marston and Snowboots led some people to call the operations Marston and Snowboots, others stuck to the script. Brigadier General Paul Williams, CO of the American Troop Carrier Command (TCC) that provided most of the glider-towing and para-dropping aircraft, sent a warning signal on D+1. It colourfully further encoded the codewords, by embedding them in jargon, including baseball-speak. After all, American baseball terms would surely confound any Nazi listeners. British cricket terminology would probably have worked equally well, but Williams was not British. He wrote:

“BALLGAME tonight MACKALL is pitcher? The GLUTTON will NOT show.”

If you’ve been paying attention, and all this confusion has not made your head spin, you will know that this message means: “Be ready to send American airborne Combat Team 2 to drop by parachute tonight to reinforce the men of the first drop. As for the British parachute assault on the bridge near Augusta, it will not be going in tonight.”

Operation Ladbroke

Operation Ladbroke did not suffer from the same problem with last-minute codes for timing signals, because the date of the operation was fixed. There were however other codes. One indicated the capture of Syracuse: “Buckhorse Five”. There were also codes for the Ponte Grande bridge on the approaches to Syracuse. “Committee One” meant the glider troops had captured the bridge [story], while “Committee One Down” meant the Italians had blown the bridge up. Similar codes existed for the capture of the bridges leading to Augusta (“Snowboots One”) and Catania (“Marston One”).

These Operation Ladbroke subsidiary codes may not seem too confusing. Potentially very confusing, however, is the fact that Operation Ladbroke itself was the victim of a mistakenly applied name. In many documents the operation was called Operation Bigot, or Operation Bigot-Husky. This may be because these names fulfilled a need by filling a vacuum, as at first there was no other codename for the glider assault on Syracuse. Before the operation, for example, documents referred simply to “Operation against Ladbroke (codename for Syracuse)”, or “Operation D-1/D (Ladbroke)”.

This evolved in some planning documents into “the Ladbroke operation”, which is not the same as officially designating it Operation Ladbroke (any more than, say, an operation called “the Syracuse operation” would necessarily be named Operation Syracuse).

After the operation, initial reports made no mention of an Operation Ladbroke, referring to it, for example, as “the recent mission”, “the first operation” or Operation Bigot. It was not until a month or so after the operation that some reports began referring to Operation Ladbroke.

At the same time, a US 82nd Airborne Division report on “Airborne Operations Husky and Bigot” was dutifully submitted to highest headquarters and ultimately reached the War Office. Somebody there who read it underlined the word Bigot and wrote in the margin in blue chinagraph pencil: “Who won this battle?” He was referring wryly to the fact that there was no such operation. He probably also knew what Bigot really meant.

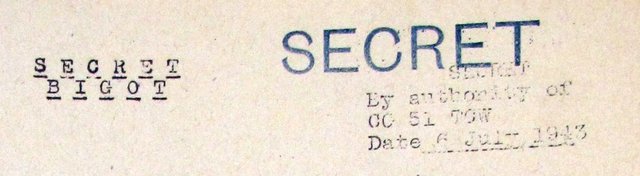

Messages were still being classed Bigot right up to the invasion. This header of a now declassified document from 6 July 1943 was issued by 51 Troop Carrier Wing, which towed most of the gliders in Operation Ladbroke.

Bigot

So what did Bigot mean? And how did it come to denote, variously and confusingly, different operations to different people? Some used it to mean the whole operation (Husky), some used it to mean all the airborne operations in Husky (both American and British), others thought it meant the operations of the Allied Tactical Air Force. Some thought it meant just Operation Ladbroke.

I have not yet found any original instructions which spell out in precise detail how the codeword Bigot was supposed to function, but we have circumstantial evidence in the records. The appearance of the word Bigot on a document meant that its level of secrecy was the highest, and it needed to be handled with the greatest of care from a security point of view. All Bigot signals were encrypted without question, for example. Only a select few people at a select few HQs were entitled to handle Bigot material. These people were recorded on a Bigot List. Perhaps these officers went about asking : “Are you Bigoted?”

Later, more and more people needed to see documents about the invasion, in order to plan how to perform their parts in it. So further lists of names were compiled, which worked on a similar principle to the Bigot List. Thus people on a list cryptically called the “XO List” were entitled to know everything about the invasion, while lesser mortals on the “YO list” were only entitled to know about some aspects of it. Some say there was also a “ZO List”. If so, it is hard to imagine how tiny were the access privileges of the people on it.

There may not have been an operation or a battle officially called Bigot, but there were some battles about the Bigot system. The minutes of meetings held in the highest HQs refer to its difficulties. The basic problem was caused by all the extra effort that Bigot material entailed. One officer complained that clerks were promiscuously rubber-stamping documents as Bigot that should not have been. They were not Bigot documents because the typescript did not contain the word Bigot.

This was an issue because the word Bigot on a signal automatically caused all the replies to it to become Bigot, even if those signals contained no secrets. Thus a one word reply to a Bigot message (such as “No”) meant that the reply itself automatically became Bigot. Worse still, any attempt to subdivide the daily flood of signals into useful groupings by subject was scuppered when Bigot documents forced the opening of a separate folder held in a different manner.

These things loomed larger at the time than they would seem to merit now. According to General Eisenhower’s head of Intelligence at AFHQ (the supreme headquarters for Husky), the inter-allied harmony between British and American staffs neared meltdown during a dispute over whether to replace the British classification “Most Secret” with the American “Top Secret”. More practically, an officer pointed out that security was all well and good, but if it meant that you did not know enough to do your job properly, it risked undermining the very invasion it sought to protect.

Bigot-Husky

Any document that was to be treated as Bigot had to have the word Bigot in it at the top of the page. This led to early planning documents for Sicily being headed, for example, BIGOT – HUSKY. The addition of Husky was needed to differentiate it from other operations being simultaneously handled (and filed) at the same HQs. These included Operation Torch (the invasion of Morocco and Algeria), followed by the campaign in Tunisia, and, later, the invasion of the Italian mainland. If there had indeed been an operation called Bigot, its documents would surely have to have been headed BIGOT – BIGOT.

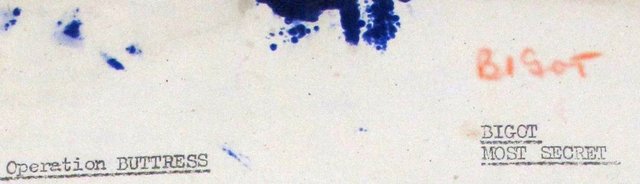

The header of a now declassified document about Operation Buttress, which was planned for the invasion of the Italian mainland after the conquest of Sicily. A quick-reference Bigot label has been added in red chinagraph, and it seems somebody has had an accident with their bottle of Quink Royal Blue ink.

Of course, by definition, anybody not on the Bigot List had no idea what the word Bigot meant. When these benighted individuals were eventually included in the wider lists (e.g. XO, YO), they began to see documents relevant to planning their own roles in the invasion. It seems that they then inherited, or glimpsed, or heard about documents by the Bigot planners, which were of course headed BIGOT – HUSKY. Apparently the newly-initiated men assumed, in the absence of any other codenames, that either the whole invasion was codenamed Bigot-Husky, or just their part in it was.

And it wasn’t just people lower down the security chain. The war diary of the British 1st Airborne Division records that the first time its brigade commanders learned about the invasion of Sicily was when their commanding officer, Major General George Hopkinson, briefed them on what he called Operation Bigot. Similarly, the senior officers of the US 82nd Airborne Division were at the same time referring to “the Bigot Husky operation”.

Does it matter? The glider operation against Syracuse is now known as Operation Ladbroke, even if the name did not gain universal acceptance until after the operation. Meanwhile, only researchers examining old documents are going to come up against the should-not-have-existed codenames Operation Bigot and Operation Bigot-Husky. At the time, ordinary soldiers believed them to be the correct names for their operations, and they seem to have served their purpose. The mistake did not impede the men’s performance in the following fighting.

Still, the history of the codename Operation Ladbroke and other airborne codewords makes a colourful tale. It’s an ironic twist to the familiar story of the fog of war, that in the attempt to confuse the enemy, security measures risk confusing the side that creates them.