The town of Augusta in Sicily did not fall easily, despite half its garrison having fled. Lance Corporal Jim Fern of the 6 Seaforths died fighting in the battle to capture it. The young pit worker from the Leicestershire mining town of Coalville was buried on the battlefield, far from home and those he loved. His grave in an olive grove overlooked the blue Mediterranean and the town he never reached.

We can piece together the story of his death in 1943 in the battle for Augusta, and of his years in the Army, from unit war diaries, and also from ten letters sent to his sister Violet. Nine of these are letters from Jim himself, and one, with the bad news, is from his friend Harold.

In 1940 Jim was in the Leicestershire Regiment when he and many other men were posted to the 6th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders, which had been decimated during the fighting in France. The 6 Seaforths was one of three battalions in 17 Brigade, itself one of three infantry brigades in 5 Division. The other two battalions in 17 Brigade were 2 Northants and 2 Royal Scots Fusiliers. 17 Brigade would later form the spearhead of General Montgomery’s Eighth Army during Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943. During Husky the job of the brigade was to race up the coast and capture two ports: Syracuse (codenamed Ladbroke) and Augusta. The ports were crucial to Eighth Army’s success, and indeed survival. Without them, it was feared, reinforcements and supplies could not be landed quickly enough to enlarge the beachhead and defend it from strong enemy counterattacks.

Military Odyssey

Back in 1941 the invasion of Sicily was still two years away, and during those two years the 6 Seaforths, and Jim with them, went on an extraordinary odyssey. First the division was sent to Northern Ireland in case the Germans invaded Eire. Then in early 1942, the brigade moved to Surrey and was told to get prepared for a tropical climate. Following the entry of Japan into the war a month or so before, it was assumed this meant India or the Far East. Realising that he might never see his family again, Jim sent a contrite letter to Violet, apologising profusely for not having put time aside to see her on his last leave.

Two weeks later, on the eve of departure, he wrote again. To add to his forebodings about departure, he’d heard that a friend in another unit had been killed, and it drove home the dangers he was about to face. He hoped his own death, if it came, would be quick, since “to be killed outright is a lot better than suffering”.

A few days later 17 Brigade left Liverpool in a convoy bound for South Africa. The Mediterranean, and hence the Suez Canal, was effectively closed to the British. This was especially true at the Sicilian Narrows, where Sicily and Africa are not far apart, and where Axis aircraft made the passage of Allied shipping almost suicidal. One of the benefits from the later invasion of Sicily was the clearing of this threat. Meanwhile all the forces intended for Egypt or the East went round the Cape, adding thousands of miles to the journey.

When the convoy reached Durban in South Africa, the troops were told to prepare for an imminent amphibious assault landing. They were not told where, but clearly they were not going straight to India. The men of the brigade had not practiced with landing craft, and were unfit after weeks at sea, so a crash course of training followed for a few days.

Invasion: Madagascar

In an undated letter, possibly written in those empty hours just before the attack, when time on a troopship drags interminably, and men file wills, or give letters to their friends to keep “just in case”, Jim reassured Violet: “Keep smiling and I’ll do the same. If there are any tough times I’m accustomed to it, should be a change from pit work”.

By dawn on 5 May 1942 the ships were anchored off the island of Madagascar. The men were crowded at the rails of the passenger liners, cheering as the leading waves of landing craft full of Royal Marines headed for the beaches. The island was in Vichy (pro-Nazi) French hands, and Britain feared that the French might welcome Japanese naval forces into the Indian Ocean, so the island had to be taken. The next day, foreshadowing the invasion of Sicily, the brigade made a long and gruelling march in full kit through suffocating heat and dust. On reaching their objective, the battalions assembled south of Antsirane (now Antisiranana [map]), a heavily fortified town that guarded the superb naval harbour at Diego Suarez.

When night fell, the Seaforths launched a bayonet charge into the defences. James Stockman, who was in ‘A’ Company (Jim Fern’s company), later wrote that the French, Senegalese and local defenders fought ferociously, and there followed the most savage hand-to-hand fighting he ever encountered. Despite Jim’s blithe comments in his letter, Violet would have known that even the toughest of times in the mines did not compare to times like these, and she would have feared for him all the same.

The men of 17 Brigade overwhelmed Antsirane’s defences, and the 6 Seaforths were present on parade when the French formally surrendered. When Jim later wrote to Violet from Madagascar, he did not mention the fighting, presumably so as not to worry her. But the mere fact of his letter let her know he was still alive, so his tone was upbeat and he merely joked about the stifling weather, and what a shock it would be to return to cold, gloomy England and a job in the pits.

The Defence of Iraq

Only a month or so after the landings, in June, the brigade headed for India, and then halfway across it, to defend India following the successful Japanese invasion of Burma. Three months later, in September, they headed back the way they came. They were now part of Tenth Army, also known as Paiforce (Persia and Iraq Force), which was sent to Iraq and Iran to counter the German threat to the oilfields of the Caucasus and Middle East. There was also the danger that the Germans might attack the British in Egypt from the east as well as from the west.

In October, Jim wrote from Paiforce that he had not seen any mail from home in six months, and was desperate to hear from his family. The normal, seaborne mail may have failed to catch up with the brigade’s constant and exotic travels, so Jim sent an airgraph that would reach the UK quickly, perhaps in time to get replies before he moved again. It seems he got on better with Violet than he did with his parents, who he said were always too busy working, but he ended his letter clearly missing them all, especially his nephew, Violet’s toddler Dennis, or “Dinkie”:

“How’s wee Dinkie getting along? Does he still give his Grandad his patter? I liked to hear him, in fact I had many a good laugh at him, oh, if you see his Grandma just let them know, I want to be hearing from them.”

Operation Husky

Shortly after Christmas 1942 the brigade was on the move again. Jim wrote to Violet that he was now enjoying the constant travel. He was contented being abroad, he said, and feeling both healthy and lucky. By May the brigade was at the Combined Operations Training Centre in the desert at Kabrit [map] in Egypt. Here, on the shores of the Great Bitter Lakes, they practised endlessly in landing craft for the next great amphibious invasion, that of Sicily, although of course the men did not yet know their destination.

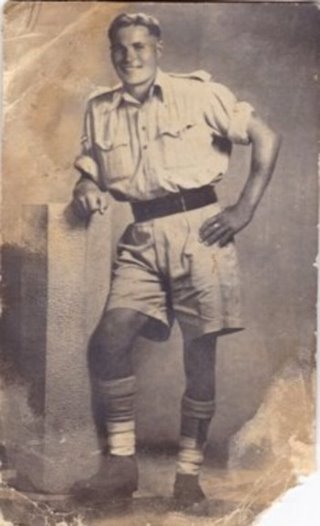

Portrait photographs were vital both to families and soldiers during the war. Like letters, they were yet another small link, another small bulwark against the possibility of imminent death and oblivion. On 30 May 1943 Jim sent Violet a photo of himself, perhaps taken in Egypt, and asked her to arrange for copies to be made of another photo that he thought was better.

It was the last letter he ever sent her.

By June the brigade was in the Gulf of Aqaba [map] in the Red Sea conducting full-scale rehearsals for Sicily. Some three weeks later, on the evening of 9 July 1943, the men of the three battalions were anchored off George Beach [map], south of Syracuse in Sicily. The night was full of the drone of bombers and long streams of transport aircraft towing gliders packed with troops. The popple and thud of distant gunfire drifted across the water. The darkness was lit by tracer, flares, searchlights, fires and explosions. The men counted down the long minutes until they had to climb into their landing craft and head for the contested shore.

D Day Sicily

On the day of the landings, 10 July, the 6 Seaforths led the landings and the attack on the nearby town of Cassibile [map], which they captured. Syracuse [map] was then taken by the Northants and Royal Scots Fusiliers, with help from the glider troops of Operation Ladbroke. The next day, the 11th, the Northants and the accompanying Sherman tanks of 3 County of London Yeomanry [photo] were held up south of the town of Priolo [map], north of Syracuse. Here, for the first time in Sicily, the British encountered German forces. The Germans were equipped with first class anti-tank weapons and armoured vehicles, and several Sherman tanks were knocked out [photo].

By the morning of the 12th, the day of Jim’s death, the Germans had pulled out of Priolo. It seems they withdrew because they guessed that the British were planning to use maximum firepower against them, including the much-feared heavy guns of the Royal Navy. The German plan presumably did not include being annihilated pointlessly. Instead they were fighting delaying actions while strong reinforcements gathered further north in better defensive positions. Their decision to evacuate Priolo was wise – the British plans did indeed include a barrage by all the divisional artillery, and also a bombing attack by 36 Kittyhawk fighter-bombers [photo]. The barrage was cancelled just in time, but it was too late to cancel the air attack, which went ahead. Two planes collided and fell in the sea, with only one of the pilots surviving.

Both 15 and 17 Infantry Brigades now entered the town, which was soon crammed with British troops and vehicles heading north along the narrow coastal plain. The congestion made a perfect target for enemy artillery, which could fire blind, by the map, and still have a high chance of hitting something. The 6 Seaforths suffered some minor casualties in the crowded streets, although other battalions fared worse. But capturing Priolo town was little in itself. Just north of it was a river that made a natural anti-tank obstacle [map], and it was covered by enemy troops ensconced on a small ridge or knoll [map]. They were supported by guns firing on the British flanks from the slopes of the foothills of the plateau further inland. It took until nearly 2pm to drive the defenders from the knoll, after a hefty artillery barrage supplemented by naval gunfire, followed by a three-company set-piece attack by the Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Battle on the Marcellino

At this point the 6 Seaforths again took over the lead. They were finally in the open country north of Priolo, and for some miles they met no opposition. However after crossing the Marcellino River [map] they entered the area behind Cugno Point [map], which faced the town of Augusta on its peninsula [map] across the bay. The area was overcast with black smoke from scores of burning fuel oil tanks, set on fire by retreating Italians (there are still oil tanks there today [map]). The Italian command, control and communications seem to have been in chaos. The oil tanks had been blown on the first day of the invasion, when the rumour spread through the local Italian garrisons and militias that the British were already at Priolo. Many of the Italians abandoned their positions and gun batteries and fled north. In fact the British did not enter Priolo for another two days.

Now that the British really were at Priolo, the Italians sent a regular army unit, the 2nd Battalion of the 76th Regiment of the Napoli Division (2/76), into the void vacated by the militias and the Germans, and told them to face east, towards the sea off Cugno Point, in case the British attempted more amphibious landings. It seems incredible that the Italians did not know that the threat was from the south, from the land, and almost upon them. Perhaps they were distracted by the numerous Royal Navy ships off Augusta, which were liberally shelling the coastal defences and towns, and also attempting to enter the harbour [story].

What followed next was like an encounter battle, when two opposing forces marching towards each other bump into one another, and then feed units ad hoc into the fray as fast as they come up. The Italians were still deploying to face the sea when the leading company of the 6 Seaforths, presumably preceded by Bren carriers [photo] in their reconnaissance role, hit the Italian “right” flank. Even then, the commander of the Napoli troops did not suspect a major advance from the landings two days before, but thought that the British must have made a landing on the nearby beaches earlier that day, and that his men had arrived too late to stop it.

This was the first time that a British battalion in Sicily had met an Italian regular army battalion on almost equal terms. The 2/76’s sister battalion in the Napoli Division, the 1/75, had been encountered on 10 July south of Syracuse, but then it had been up against three or more British battalions, and it was effectively destroyed. Now the 6 Seaforths, deployed in single file along the road north, came under machine gun fire from both sides. Italian mortars and artillery plastered the road and the approaches south of the Marcellino [photo].

The Seaforth mortar platoon was ordered forwards to lend weight to the attack, but it could hardly move along the narrow and heavily congested road. Part of the blockage was the large Sherman tanks [photo], which also could not get forwards quickly. The RAF was not available for on-call close air support, and the Royal Navy was by now fully occupied with trying to get its ships into Augusta [story]. In any case, the ships would have had the same problem as the British artillery – the opposing forces were too closely intermingled to allow for safe shellfire. So ‘A’ Company, Jim Fern’s company, attacked without support. As a single company facing a whole battalion, progress was slow. James Stockman later described the fighting as “grim”.

Dash and Courage

Then the British Bren carriers [photo], showing great dash and courage, decided to charge madly down the road and see if they could break through what they hoped was a thin crust of disorganised Italian defenders. Disorganised it may have been (from facing the wrong way), but 2/76 was not a thin crust. Also, its commander had the foresight to bring one of his artillery pieces down to the road to act as an anti-tank gun. Here it did exactly what it was supposed to, and knocked out the one of the carriers. Three men were killed. The other carriers now came under a hail of hand grenades. The carriers were open-topped and only lightly armoured, and they were forced to withdraw.

By now the Sherman tanks had come forwards, but they were withdrawn again because of the anti-tank guns. This was probably not out of some kind of cowardice. The Sherman crews had shown their courage the day before at Priolo, and would do so again the next day, when they lost six out of seven tanks attacking a strongpoint. But warfare is like a game of stone-paper-scissors. In a case like this, simplistically: machine guns kill infantry, tanks kill machine guns, anti-tank guns kill tanks and infantry kill anti-tank guns. So ‘A’ company of the 6 Seaforths bore the brunt.

The fighting went on in spurts for several hours, as each side assembled enough forces, or reformed for another attack or counterattack. ‘A’ Company, Jim’s company, was relieved by ‘B’ Company. At one point the Seaforths were bombed and strafed by a dozen Italian fighters. These planes were then called away to escort aircraft carrying those strong reinforcements that the Germans were planning to use further north. The reinforcements were elite German paratroopers, who were about to be dropped near the Primosole Bridge over the Simeto River south of Catania. The plan worked, and the British, following the capture of Augusta, were held up south of Catania for many days.

Meanwhile, back on the Marcellino, the British mortars finally came forward to tip the scales in favour of the 6 Seaforths. In any case the Highlanders were battle-hardened troops, while the Italians of 2/76 were green. By the time the battle was over, and the Italians had retreated, it was early evening, and the sun was sinking. On the other side of Augusta, the men of Britain’s elite SAS Regiment were landing under intense fire [story] to seize the town itself, which had been almost completely evacuated by the Italians.

Fight for the Seaplane Base

One final phase of the battle for the approaches to Augusta remained for the 6 Seaforths – the battle for the defences around the Italian seaplane base [map]. This was located in the armpit of the bay that curves round and connects with the peninsula town of Augusta itself. The area was (and still is) immediately recognisable by its huge airship hangar [map], which towers above the shore. It was protected by a variety of defences including pillboxes [photo]. It was probably dark by this time, with a crescent moon providing enough light to fight by.

The Sherman tanks of the Yeomanry were now working hand-in-glove with the infantry, and had come up with a way of dealing with blockhouses that might harbour anti-tank guns, without unnecessarily exposing the tanks. Their new technique involved the commander of the tanks walking forwards with the infantry. When the heavy machine gun of a pillbox opened fire, he called forward the leading tank and briefed it. It then fired three armour-piercing shells, followed by three high-explosive shells, then pumped long bursts of machine gun fire at the pillbox. Since the concrete in most pillboxes in Sicily did not use steel reinforcement, and the coastal troops manning them were mainly older reservists with poor morale, this usually had the desired effect. However, near the airship hangar [map], a pillbox resisted. It was taken by 10 Platoon of ‘B’ Company supported by tanks. Six Italians died inside it, three outside. No prisoners were taken.

Jim’s Death

It may have been here that Jim Fern died, attacking the pillbox, as described by his friend in ‘A’ Company, Lance Corporal Harold Halford. We cannot be sure, because the 6 Seaforths war diary and Harold’s account do not quite tally. War diaries are not infallible, but it states more than once that ‘B’ Company was in the lead at this point, and we know from his last letter that Jim was in 9 Platoon, ‘A’ Company. Perhaps, then, Jim was killed in the battle near the Marcellino river, in amongst the thorn scrub and the oil tanks, when ‘A’ Company was in the lead. However neither British nor Italian intelligence maps show any pillboxes near the Marcellino, nor do accounts mention any, but Harold specifically mentions a pillbox.

We will probably never know for sure. However we can with some certainty say that Jim probably died between about 4pm and midnight on 12th July 1943, somewhere between the Marcellino River and the area around the seaplane base.

Not long after the fighting for the houses and pillboxes near the seaplane base, the 6 Seaforths stopped for the night. In the last three days they had made an assault landing, marched many foot-sore miles in stifling heat and dust, plagued by flies and malarial mosquitoes, been shelled and bombed, and fought in gruelling conditions. Their sister battalions now took the lead, and in the small hours of the morning they marched past the isthmus of the Augusta peninsula and occupied the high ground north and north-east of the town. Italian civilians who had been evacuated from Augusta onto the heights of Monte Tauro were astonished to wake up and find the Royal Scots Fusiliers camped nearby [story]. The Northants connected with the SAS in the town in the morning. Apart from the mopping up of bypassed enemy positions, the battle for Augusta was over.

We may not know exactly when or exactly where Jim died, but Harold’s letter tells us, as it told Violet all those years ago, what we want to know:

15 Aug 43

Dear Friend

[…]

Jim was lost 2 days after we landed. We were making an attack on a pill box on the outskirts of a town which later fell to us. They got old Jim with machine gun fire. He died a few minutes after, but I am thankful that he felt no pain.

Jim went into the attack as he had done many times before, with no fear at his heart, his only thought to do his duty as a soldier and obeyed orders to the last. I saw him shortly after he had passed away. He had a peaceful look on his face. But I could not stop with him long, circumstances would not allow it as you will understand.

[…]

There is one more thing I should like to mention, he had his girl’s photo next to his heart when he died and also a bone ring with her photo encased in it. Well I know you would like to know where Jim’s last resting place is, he is buried on the top of a hill overlooking the town and his grave is under an olive tree not far from the sea. He is resting in a lovely surrounding. A rough wooden cross with his name on marks the spot. He is not alone, about 7 of our comrades are around about him. […] He died as every soldier likes to die. Fighting.

[…]

From Jim’s old pal

Harold.

Jim’s body was later moved to the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Syracuse [map]. The bodies of all British and Commonwealth soldiers that had been given battlefield burials were transferred to cemeteries. A standard gravestone of a uniform design was provided by the government, but relatives could specify a personal message to be carved onto the base. Jim’s heart-broken parents, Charles and Grace, wrote this for their son:

HAPPY, SMILING, ALWAYS CONTENT

LOVED AND RESPECTED

WHEREVER HE WENT.

With thanks to Mark Boulton.

Jim Stockman’s book “Seaforth Highlanders 1939-45: A Fighting Soldier Remembers” was published by Crecy Books in 1987.

Dear All, what a great site and helpful in establishing the events leading to the loss of JJ Marshall, Pte, 4805403, 6th Bn Seaforth H., who died aged 27 on the 13 July 1943. John James Marshall is one of the 168 fallen of WW1 and WW2 listed on the parish memorial of St Matthews Northampton, part of a military history study for the church, and will be remembered during this years remembrance events. His headstone citation reads – “We loved him well God loved him best and called him to eternal rest”. Kind regards, Martin Stone

Thanks Martin.

Thanks for the information

My wife’s Grandfather died on the 12 July 1943 and is buried in the same cemetery.

Corporal Charles Woodward his number is 2827194

WOODWARD, Corporal, CHARLES, 2827194. 6th Bn., Seaforth Highlanders. 12 July 1943.

Age 29. Son of William and Annie Woodward, of Liverpool; husband of Ellen Woodward,

Looks like he may have been with Jim when he died ?

Do we know how many of his battalion would have died that day ?

Thanks

Thanks Rennie. CWGC records for 12 July have five names in Syracuse and none in Catania or Cassino. It is of course possible that others died later of wounds received on the 12th.

Many thanks for this vivid and moving description. My late father, Frank Devaney, was in the Seaforths and was with Jim’s unit and made all of this journey. He was wounded later in Italy at Casino having also been evacuated from Dunkirk beach on a stretcher. Like most he told his family very little of his war activities.

Thanks Michael. Comments like yours make my day.

Thanks Ian for your work. Helps paint a very vivid picture of the period. My great uncle James Mchardy died 2 days later than Jim Fern; they must have served together. We’re visiting the war grave at Syracuse this week and your article has really brought this to life.

Thanks very much Ian