After the failures of Operation Ladbroke, recriminations flew in every direction. The glider pilots were not exempt. Surprisingly, their own commander later blamed them the most.

“It was … the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life”, the victorious Duke of Wellington famously said after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The same could be said about the Battle of Waterloo Bridge in 1943, when glider troops, including glider pilots, captured the Ponte Grande bridge south of Syracuse in Sicily. The bridge was codenamed Waterloo, and the glider men, although ultimately forced to surrender, heroically held it against the odds just long enough to prevent its destruction by the Italians. But the cost was terrible. Scores of gliders landed in the sea and hundreds of men drowned. Were the glider pilots to blame?

At first, no glider assault was planned for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in the summer of 1943. The focus was entirely on paratroops carried in troop carrier planes. So much so, that Allied senior commanders agreed early in 1943 that the success of the entire invasion would depend on the skill of the troop carrier pilots. The logic was as follows.

The Italians were fighting hard in North Africa and could be expected to fight just as hard for their homeland, where they would also be backed by crack German divisions. It was crucially important to capture ports rapidly so that the landings could be shored up against counterattacks from strong Axis mobile units. But the ports were too heavily defended to be attacked from the sea, so they would have to be attacked from the land by troops coming ashore at nearby beaches. So it was essential get the troops off those beaches quickly.

But these beaches were thought to be stiff with mines, barbed wire and concrete pillboxes, and covered by coastal gun batteries. It was believed that naval gunfire and air attack were, for various reasons, unsuited to the task of suppressing the beach defences effectively. Therefore, the beach defences must first be “softened” by airborne troops. This meant that paratroopers would first have to be delivered to drop zones (DZs) near the beach defences, so they could complete the “softening” before the naval landing craft approached the shore.

But the paras would have to be dropped at night at the last possible moment, so as not to lose too much of the element of surprise. This meant there was no margin for error, and pin-point accurate navigation was required from the pilots of the troop carrying planes. Otherwise the paratroopers would not reach their targets in time to make any difference. And this was why the entire invasion was thought to hinge on the navigation skills of the transport pilots.

For airborne support was deemed “vital”. In this context, Major General ‘Boy’ Browning later ruefully described “vital” as “that dangerous word”. He was the founder of the British airborne forces and ex-commander of 1st Airborne Division, which was providing the British paratroops and glider troops for Operation Husky. He was poached from the division to become Airborne Adviser to the Commander-in-Chief of the invasion of Sicily, General Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower had signalled the Chiefs of Staff as early as February: “Consider that employment of 5 Parachute Bdes [brigades] is essential part of present outline plan. If Allies resources will not meet requirements stated above, effect on plan & chances of success must be examined without delay”.

There were grave doubts. The Allies chief planner reported that he “was seriously disturbed by a report given him by his senior air staff officer to the effect that, from the point of view of night flying & navigation training, it would not be possible to use paratroops in the method envisaged”. Browning himself thought the “softening” plan was crazy, but it was not his call. Instead he was left with the job of trying to chivvy along that vital training.

Transport Pilots

Most of the available US transport crews had little or no operational experience of airborne assaults (the US was providing the bulk of the planes, because there were not enough British ones). Some of these planes had dropped paratroopers during Operation Torch, the American landings in North Africa, but here, as Browning noted, “In spite of the gallant efforts of the aircrews, the drops were inaccurate and men widely dispersed”. The problem was that the main function of the transport planes was transport, not combat. Browning later quipped: “It is very difficult for crews who have been taking up squadrons’ pianos & easy chairs to suddenly switch over to operations”. This was unfair, especially the implication of a frivolous lifestyle, as any officers’ mess anywhere aspired to such things. In fact the transport planes’ day to day tasks were critical to the war effort, and little time was spent ferrying their own units. Browning was clearly exaggerating for effect, but the basic point held – it would indeed be difficult to switch from ferrying to combat.

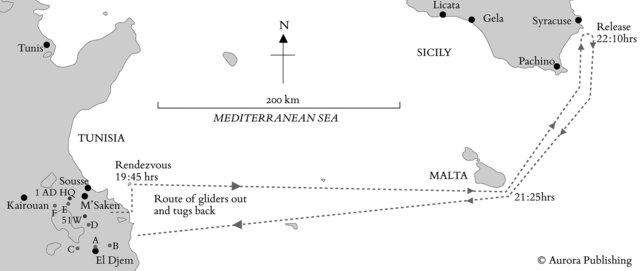

The US transport pilots were mainly used to flying by day, well away from enemy threats, using direction-finding radio signals and homing beacons. Most crews did not even have a navigator. This lack of navigators would force the planes to fly to Sicily in tight formations of four, with the only navigator in the lead plane. If a formation broke up from mistakes, bad weather or enemy action, then three planes could get lost. Clearly, even with a navigator, crossing a coastline largely devoid of unique landmarks, at night, dropping paratroops in a tiny area of enemy territory, blinded by searchlights and being shot at, after a journey of hundreds of miles over water, was a task that would require a great deal of preparatory training. Also, formation flying is not easy, especially at night, and that would require lots of practice too.

But it wasn’t just that there was a shortage of suitably trained and experienced aircrew. There was a shortage of transport planes overall, and every one, whatever the skill of the pilots, would be needed. The British, with their straitened wartime economy, had never developed a specialist transport aircraft, and were reliant on obsolete or obsolescent bombers for parachute dropping and glider towing. These were only grudgingly released from the strategic bombing offensive against Germany, so there were not many of them. Instead both the US and British airborne forces depended heavily on American C-47s (known to the British as the “Dakota”). Based on the DC-3 civilian airliner, these were adapted both to carry paratroopers and tow gliders.

Thanks to America’s massive industrial capacity, the C-47 was available in much greater numbers than the parsimoniously parcelled-out British bombers, but in the Mediterranean the C-47s were already fully employed transporting freight and ferrying important personnel. The number that could be spared for airborne work was still not enough to carry all the paratroopers the planners wanted, and this led to the invasion being phased in stages, with first the British using them and then, on another day, the Americans. This was so that the aircraft which survived dropping paras on the first day could drop further waves on subsequent days. The bottom of the barrel was scraped in an attempt to find more planes. Suggestions included curtailing freight shipments over the Himalayas to China and reducing the scheduled civilian flights of BOAC (the forerunner to British Airways).

The Plan Changes

Such was the importance of the airborne role in the plan that the date of the entire invasion was worked out to suit it. The need to avoid losses among both the planes and the paras dictated a night drop. The Navy and Army wanted no moon during the seaborne landings, so they could approach in darkness and make less obvious targets. However the transport pilots needed as much moon as possible to help find the DZs and drop their paras accurately. So a compromise was chosen, with a crescent quarter moon at the time of the airborne drop which would have gone down by the time of the seaborne assault some five hours later.

This was an unhappy choice for both parties. The quarter moon did not give the pilots enough light on the first night, while the Navy ships had to stay just offshore for several days and would be lit by the growing moon, making them easy targets for nightly Axis air raids, which in turn would be harder to spot and destroy. This compromise narrowed the possible dates to a few days roughly a third of the way into each month. Prime Minister Winston Churchill asked for June, but there was no way the airborne (or even seaborne) divisions would be ready by then, so D Day Sicily was finally set as 10 July 1943.

At first, while the initial planning was being undertaken, there was still heavy fighting in North Africa. The Allied generals who would be commanding the US and British task forces in Sicily were too busy commanding their armies in Tunisia to give any time to planning the invasion. It was not until late April, with the end in Tunisia clearly in sight, that General Bernard Montgomery, commander of the British 8th Army, got seriously involved. He strongly objected to the Sicily plan and, amid much uproar, forced it to be recast. It was at this time that the role of the airborne changed.

No longer were the airborne troops to be landed behind the beaches to “soften” the defences. No longer would the British get all the planes to themselves at the start of the invasion. Two thirds of the available planes were given to the US 82nd Airborne Division for drops at the same time as the British airborne drops, but in a different sector. The greatly plane-depleted British airborne were now divided up to be dropped on three successive nights to hold open three bridges and the approaches to three Sicilian ports: Syracuse, Augusta and Catania (these towns were codenamed Ladbroke, Glutton and Fustian respectively). The ports were desperately needed so that shipping could quickly land enough supplies and reinforcements to keep the British bridgehead safe from counterattack, and to keep it expanding.

Under the previous plan, no significant use of gliders had been imagined. Some had been earmarked for landing alongside the paras to bring in anti-tank guns and light artillery. Mainly, however, it had been envisaged that most of the gliders might be used to land follow-up waves of air landing troops on captured airfields to reinforce the bridgehead. Now, following Montgomery’s changes, a far more strenuous role was expected of the gliders.

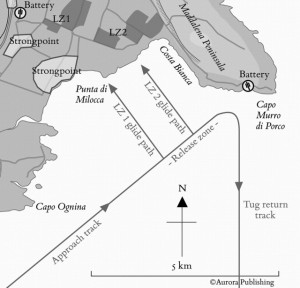

They were to be used in the front line in the first of the three British airborne assaults. It was another decision reflecting the shortage of transport aircraft and the crucial importance attached to airborne support. The gliders were to be released 3,000 yards out to sea, as this would keep the precious towing aircraft away from anti-aircraft fire, so more would be available for the subsequent parachute drops. These were far more dangerous, as they entailed the planes flying low and slow directly over the DZs in the teeth of point-blank enemy anti-aircraft fire. Losses of planes of up to 50% per mission had been predicted. So the use of remotely released gliders seemed to bring huge advantages in terms of mitigating the shortage of transports. This first operation was named after its target: Operation Ladbroke.

Training Time

As if there were not shortages enough already, this late change of plan also meant that there was now a shortage of time to rectify a shortage of practice. Many of the glider pilots had graduated from advanced training in the UK months before, only to find they could not get refresher flights, and many of the rest had only recently graduated from basic training. There was also a shortage of gliders. The Waco gliders, which the Americans were supplying to the British glider troops, were still sitting near the docks in pieces in giant packing crates. Until they were all assembled, no flying could take place, and the time available for training became shorter still.

It was now so late, in fact, that there were only about three weeks from Wacos becoming available in quantity, and training having to stop for rehearsals. Significantly, there was only one period left before the attack when, for a few days, the moon would be in the same phase as on the night of the invasion, and so could be used for simulated practice. Most British glider pilots had never seen a Waco, let alone flown one, and the Waco was different from the British Horsa in several respects, in particular in its style of landing, as it used spoilers not flaps.

Operation Ladbroke, with nearly 150 gliders lined up to go, would be the first ever glider attack by night. It would also be the first mass glider assault by Allied forces, even bigger than the German mass glider operation in Crete in 1941. With the better part of two US and British airborne divisions being employed, Sicily was in fact the first really large airborne assault of any kind by the Allies. The prior parachute drops during Operation Torch had been small by comparison.

This meant that everything was up for grabs, as nobody seemed to know anything. Eisenhower pestered the Chiefs of Staff in Washington DC about the state of training of the US 82nd Airborne Division (then still in the US), wanting to know what it was capable of, so he and his staff could decide how to use it. Urgent messages flashed between senior officers, even airborne specialists, trying to establish the maximum carrying capacity of the C-47 in terms of fully equipped paratroopers (the logic being that if you cannot get more planes, then cram more men into those that you do have).

There was no doctrine regarding mass glider landings by night, other than that they were probably not a good idea, but, if undertaken, would require well trained pilots, at least a half moon and navigational aids in the LZs. Which was not good news for the glider pilots, who had had little night training, and who would be landing in a quarter moon with no navigational aids whatsoever. Suddenly, the success of Operation Husky seemed to hinge not just on the training of the tug pilots, but also on the training of the glider pilots who were to spearhead the entire invasion. The pressure was immense.

In the short time left to them, the British glider pilots would now not only have to convert to the Waco, refresh their flying skills, practise their landings, and master doing all this at night, but everything about the operation had to be worked out from scratch. How should the planes and gliders best be marshalled for efficient take-offs? What formation should they fly in? What route should they take to Sicily? How would they recognise the release points? How could scores of gliders land quickly and safely in a small LZ? At what height and distance should they release? How could the glider and tug pilots communicate? What was the sink rate of a loaded Waco at different speeds? How fast should the Waco be landed? What training programme would best bring about the desired results?

The Americans, in addition to providing nearly all the gliders and most of the planes, pitched in with a will. Under the administrative auspices of the US 5th Army, bulldozers carved airstrips out of the Algerian desert and camps arose, while fuel, vehicles, drivers, mechanics, and ground crew were all supplied. American glider pilots (GPs) acted as instructors to the British GPs (and many later volunteered to fly in the attack). A much smaller contingent of RAF aircraft arrived. They were part of 38 Wing, which back in the UK was responsible for glider training, so its officers had ideas, despite limited operational experience, about how things should be done. Not surprisingly, however, considering who was now hosting the party, the officers of the American Troop Carrier Command were not keen on being told what to do.

Chatterton

But the main burden for the planning and training fell on the British 1st Airborne Division, in particular on its CO, Major-General George Hopkinson, and the CO of the 1st Battalion of the Glider Pilot Regiment (GPR), Lieutenant-Colonel George Chatterton. Quite apart from his role as a commanding officer, Chatterton is significant in the history of the GPR because he wrote one of the earliest and most seminal books about the regiment, “The Wings of Pegasus”, published in 1962.

It was in this book that Chatterton said of the failures of Operation Ladbroke: “I was under no illusions concerning the main reason for the near-disaster. Whatever mistakes I may have made, and no doubt I did make many, what I could not help was the limited training and, therefore, the limitations of the glider pilots.”

This seems an astonishing statement for a commander to make about men who were, after all, not just “the” glider pilots, but his glider pilots. There is no sign here of commonplace notions such as where the buck stops, or leaders falling on their swords. Following Ladbroke, others had more understandably pointed the finger at the glider pilots. Both RAF and American airmen said some glider pilots turned the wrong way or made unwise manoeuvres after being released. The glider pilots accused the American tug pilots of being afraid of flak and ditching them to drown in order to save their own skins. The Army blamed the flyers and the flyers blamed the Army. The Americans blamed the British and the British blamed the Americans. But if there was one person you might think you could expect to go to bat for the glider pilots, it was their commanding officer.

Instead Chatterton cited the “limitations” of his men as the “main” reason for the “near-disaster”. At first glance this seems unlikely. The debacle of Operation Ladbroke was, as in all the best foul-ups, caused by a perfect storm of misjudged decisions and unfortunate circumstances, any one of which alone might not have led to calamity. The tug crews had direct orders to release the gliders if the gliders did not release themselves, and they had clearly been ordered to preserve their planes for the coming operations. The landing zones were the best available (as Chatterton agreed), but full of hazards. Navigation aids were dismissed for a variety of reasons. Apart from the RAF bomber crews, nobody had much experience at night. The American transport pilots had little or no combat experience, and did not have enough navigators. Due to the late hour at which the operation was confirmed, training time was indeed limited. During the landings the minimal light of the crescent moon waxed and waned as hazy cloud covered and uncovered it. The weather turned against the Allies in other ways, and a near gale was blowing against the gliders as they released. Chatterton (who was frequently accused of worrying excessively) admitted that he had dithered over raising the release heights to compensate for the wind, and had left it too late. Those release heights were perilously low in the first place, deliberately so, again for a variety of what appeared, at the time, to be sound reasons.

Nevertheless the charge is that the limited training of the glider pilots was the main factor. The question is whether the accusation is true. And if not, why did Chatterton say it?

In Part 2: Post-mortems for Operation Ladbroke.

A version of this article appeared in “The Eagle”, the magazine of the Glider Pilot Regimental Association.