Flying Officer Ray Atkinson towed a Hamilcar glider in Operation Varsity. The flak over the Rhine was apparently fearsome, but he never mentioned it – only the guilt he felt that he and his crew were going back for a hot meal in the NAAFI, while his glider pilots and their troops were descending into hell.

Ray Atkinson volunteered for the RAF in 1941, aged 18. He was a modest man who never spoke of his wartime experiences until he was nearly 80 years old. Then, when he realised that his family wanted to know his story, he wrote it all down. His account describes how he was trained as a pilot in Canada and then posted to an Operational Training Unit flying Whitleys at Abingdon, where a leaflet dropping operation over France first exposed him to enemy fire. From the OTU he was posted to fly heavy bombers for army cooperation tasks. He later flew Halifaxes in support of SOE and Resistance agents all over Europe, before towing a Hamilcar glider during Operation Varsity. This is his story of working with gliders, in his own words:

March 1944: We expected to be posted to a bomber squadron but instead we were sent on courses to do airborne work. That involved glider towing, paratroop dropping and container dropping. Initially we were posted to Sleap near Shrewsbury. Again we flew Whitleys. The hedge at the end of the airfield was only about six feet high but one had the impression that one only just missed it when pulling off Horsa gliders. There Ivor Flack, another pilot who had been on the same course at Abingdon, introduced us to Totopoly. We played it frequently in the evenings when we were not flying.

The Wrekin [hill] was within the airfield circuit and we always kept that in mind when taking off and landing. In bumpy weather Whitley glider towing was quite strenuous requiring constant adjustment of rudder, elevators and ailerons. At take-off the towrope was snaked from the aircraft to the glider and the tail-gunner kept the pilot informed when the rope was tightening and finally about to become taught. He also told the pilot when the glider became airborne.

April 1944: From Sleap we went to Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at Tilstock near Whitchurch. There we flew Stirlings, our first experience of four-engined aircraft. We now were given an engineer who had a lot of responsibility for checking and managing four engines and the fuel tanks. A splendid chap, Sgt Tom Bussell, joined my crew. He was about thirty and a policeman in civilian life. Stirlings, though very large for those days, were very light on the controls. They responded about as lightly as Oxfords. They had a bad reputation for getting their extremely long undercarriages buckled. We had to land them without any twist or bounce and keep them perfectly straight until the end of the landing run. I can’t clearly remember but I think that at Tilstock we pulled off Hamilcars as well as Horsas.

August 1944: It was decided that as we were liable to drop paratroops it would be a good idea if we knew what a drop felt like. We were sent to Paratroop Training School at Ringway in Cheshire. The first few days we practised rolling on mats. Then we swung on a rope, let go, landed on a mat and rolled. We also had to sit on a box, upper legs horizontal, lower legs vertically downwards, trunks upright and push off with our hands. That was so as to be able to jump from an aircraft through a hole only about three feet fore and aft and about three feet wide. We were taken up on Whitleys to watch others jump. Then came our turn. We went up sitting looking inwards on a circular bench slung under a balloon. From 1,000ft we jumped. We had static lines which opened our ‘chutes. We didn’t have ripcords to pull ourselves as we would have done in case of baling out in an emergency from an aircraft. One felt a tremendous surge of gratitude when the ‘chute opened and for a few seconds one could bask in the delightful feeling of gazing down on the lovely fields as one fell seemingly slowly towards them. Then one had to remember to position oneself correctly in one’s straps and try to face the way one was being blown and remember what we had learnt about elbows and rolling. A fairly reasonable landing achieved.

Two days later we went up in a Whitley, this time to 800ft. One’s speed on leaving the aircraft helped to open the ‘chute. Again we had a static line and only had to concentrate on clearing the aircraft without catching our backs on where we had been sitting or knocking ourselves out by catching our foreheads on the front of the hole. Again relief when the ‘chute opened but rather less time to enjoy the scenery. I was billeted with a pleasant couple living in a private house away from the training station. When our jumps were over they told us that one of the jumpers staying with them on the previous course had broken his ankle. The old hands on the station sang ghastly songs about the various possible ways of failing to come down to a safe landing. Back to Tilstock for a day or two.

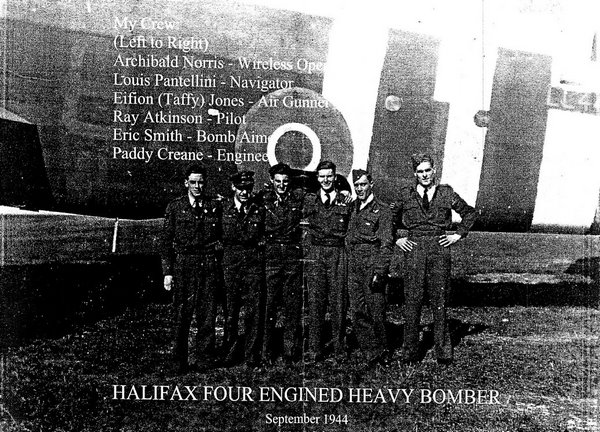

My crew and I were then attached to an operational Stirling squadron in 38 Group at Fairford. We were distributed to different operational crews to experience a container drop over France. Tragically, Tom Bussell, my engineer, and the crew he was with failed to return from their mission. We never knew what had happened. The rest of the crew all came back safely. Tom was replaced as engineer by Paddy Creane, a Southern Irishman. Training was now finished.

My crew was flown to Tarrant Rushton in Dorset to join 298 Squadron of 38 Group, a Halifax squadron. We were now ready to drop containers, tow gliders or drop paratroops. A Canadian pilot, F/O John Taylor, of my Flight showed me how to fly a Halifax. On all my previous flights I had been instructed to a final cockpit check from left to right. The code was “BUMPFF” (Brakes, undercarriage, mixture, pitch, fuel, flaps). John Taylor, however, said “Wal, Atkinson, I always check from right to left.” Single-engined propeller aircraft undergo torque. The propeller turns one way and tries to turn the aircraft the other way. The wing that would have gone down because of the torque is set at a higher angle to compensate in flight. That wing therefore stalls before the lower angle one and that can cause a spin. Twin- and multi-engined craft do not undergo torque but they suffer from tail-buffeting due to the slipstream from propellers. From Oxfords to Whitleys to Stirlings I had been instructed to open the throttles smoothly by leading them from the appropriate side against the swing. If one opened the throttles equally the aircraft would swing considerably.

John Taylor said “Wal, Atkinson, I always open up all four throttles fully immediately and compensate the swing by brake. “ Each wheel had independent braking to make taxiing easier. Anyway, he took off by his method, let me handle the controls for a while, then he did a circuit and landed. Then it was my turn. I thought “Ok, I’ll check from right to left and open up full throttle.” Opening up right away meant one knew if all four engines were working properly and one reached flying speed more quickly. It went off all right and after a couple of hours I was “converted”.

For container dropping we flew only five days before full moon to five days after. We flew fairly low to the dropping zone and dropped the containers from 1,000ft, I think. When we arrived over the dropping zone we flashed two Morse letters as briefed, and if the Resistance people flashed back the two proper different letters we dropped. If not, we were not to drop. The Resistance people laid out flare in a T formation, the stem of the T into the wind and the crossbar on the windward side. We flew over the T into the wind, thus reducing our ground speed and landing the containers fairly near the flares. We dropped over France, then Belgium, then Holland, then Denmark, then Norway as the Allied forces progressed.

Over Holland we flew very low and on one occasion I had to climb and bank to miss a windmill. Once we were just about to leave the Dutch coast on our return when we were shot at with tracer bullets. They seem to approach very slowly at first and then whizz past. I tried to weave as much as possible allowing for the fact that we were very low. We got away all right and laughed at the bad shooting. When we inspected the plane the next morning the ground-staff showed us a jagged hole in the tail plane about twelve inches in diameter. That was only about four feet from Taffy, the rear gunner’s turret. He had laughed the loudest. For Norway we flew very low over the North Sea then climbed quickly to 7,000ft to avoid the mountains. By moonlight from the air Norway is very beautiful.

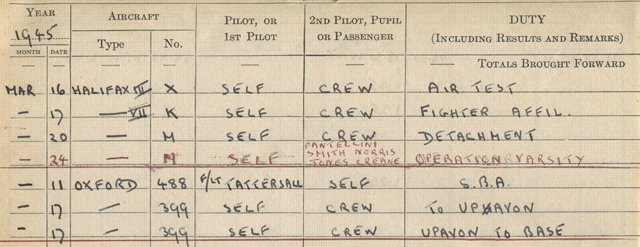

1945: From Tarrant Rushton we never dropped paratroops. We practised towing gliders, both Horsas and the much bigger Hamilcars. They could carry a small tank or goodness knows how many troops. I can’t remember much detail about Operation Varsity. We flew to Woodbridge which had a mile-long runway and where the Hamilcars were lined up. I think we were introduced to the pilot of the glider we would be towing and his troops.

John Taylor was piloting number three combination and I number four. I think about thirty combinations took off from Woodbridge. We flew in fairly close formation. Number two was behind and just to starboard of number one. Number three was behind and just to port of number two and hence in line astern of number one and so on down the line. We released the gliders a few miles the other side of the Rhine. Not long before the release number three peeled off to port. We did not know why as we had not seen any enemy fire. I moved into number three position and we released our glider at the required place. We had a tremendous respect for the glider troops who had to endure a packed journey, face a rough landing, then engage in battle. The pilot had to be an expert flyer and then join in the fighting. All we had to do was to return to a comfortable base.

The Raid Report

After the operation Ray Atkinson filled in a Glider Raid Report form. Here is a selection of answers that he gave to questions on the form:

Station: Tarrant Rushton

Serial No: 16

Squadron: 298

A/C: Halifax III

Letter & Call Sign: A.M.

Captain: F/O Atkinson

Navigator: F/O Pantellini

Flight Engineer: Sgt Creane

W/Op: F/S Norris

Bomb Aimer: F/O Smith

Gunner: F/S Jones

Glider No: 242

1st Glider Pilot: P/O Walker

2nd Glider Pilot: Sgt Knox

No. of Troops: 8

Equipment carried: 17 pdr gun & Dodge truck

LZ [landing zone]: ‘R’

Time Up: 0720

Time Over LZ: 1037

Time tug down: 1317

How was LZ recognised? Release point – lake crossed & release over LZ ‘A’.

Relation of release to LZ: 1.5 miles W of LZ ‘R’.

Release height, time & heading: 2500 ASL, 1037 hrs, 077 degrees M.

Observations by crew: 1030 hrs Stirling seen to crash after 4 bodies baled out, 5 miles W of Rhine.

.

Raid Report courtesy of Steve Wright, author of “The Last Drop”, one of the key books about Operation Varsity. The book can be bought via the publisher [here].

For other articles about Operation Varsity, see here.

Text of account and personal photographs are copyright The Estate of Ray Atkinson.

Would love more information on this article. Please contact me.

I’ll be in touch, Liz

Lovely to read this. I think the ‘Ivor Flack’ referred to was my Dad. I have a brother Terry who lives in the States now and have just returned from a visit.

Thanks for the comment June. Always happy to hear from family.

Great article … like to get in touch with you and other Varsity veterans and their families who flew from Woodbridge. I am a volunteer at the Bentwaters Cold War Museum which also covers the nearby RAF Woodbridge airfield. I’ve researched a little of Varsity and like to collect stories and info for our archive. Please drop me a line at the museum address simon.gladas@bentwaters-as.org.uk

Look forward to hearing from you.

Thanks for getting in touch, Simon. I’ll contact you soon.

Hi My Great Uncle Eric Innes flew with Robert Edick 298 sqn.Lost 25/26 Feb 1945 off Norway. WT M NA 103.Very nice site you have.

Thanks Dave

Hi Dave, My Uncle was Hector Lochhead the Tail Gunner on that flight. Interestingly my brother found the sister of Robert Edick in the early 2000s while repairing her house. Small world. Cheers Ray

Hi Raymond

I have an incredible collection of info(ops etc) that was given to me by Andrew Wright in Dorset.I will stay in touch.This is awesome I’ve spent several years wondering if any family was still around.

Cheers

Dave

Hi Dave

I gave Ian permission to give you my email. Any info would be very interesting, I don’t have much but I’ll share all I have. I’ve been going around the web doing searches to see what I could find out so this is excellent . Cheers Ray

Hi Dave, I am trying to find out more about what happened on RAF Tarrant Rushton on the 17th of september during operation Market Garden. I saw that F/O Robert Edick, the pilot of your Great Uncle’s plane, was towing Horsa C/N 357 and that he was engaged by light accurate Flak from ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

Thanks Gerrie. Do you know that the Operational Record Books for 298 & 644 Sqns (Tarrant Rushton on 17 Sep) can currently be downloaded from the National Archives for free? There are 5 relevant ones. Your note about flak comes from one, so perhaps you do. The Raid Report for C/N 357 can be found on page 113 of AIR 27/1652 [here]

nice to read, my dad was in 298 squadron at this time and when they went out to India, he was a rear gunner with them until 1946. Unfortunately for me he died last year at the ripe old age of 95.

Thanks Neil

This information is priceless!!! All to soon now it will all be lost unless recorded now.

My father Arthur Frost was a tail gunner in Sterlings and Halifaxes, he flew with 190 and then 620 squadrons. They were involved with supplying the Norwegian resistance with the where with all to successfully thwart Hitler’s attempt to produce an atomic bomb and sink the ferry carrying heavy water at Telemark.

620 squadron towed gliders to Arnhem where they lost a large number of aircraft and crew at which point 190 was merged into 620 and my father was involved with operation Varsity, I believe after release the pilot of the glider was shot and killed during the decent and all on board perished.

I knew little or nothing of his war record and only found out in his later years when I would take him to his crew reunions and his fellow crew members told me.

We lost my dad in 1994 and I believe now all but one of the boys have gone so accounts and articles such as this are solid gold

Thanks Martin

Does Ray Atkinsons log book mention a flight to Denmark April 20-21st 1945 from Tarrant Rushton? Please contact me….

Yes, Ray flew an SOE mission to Denmark that night.

My Grandfather flew on that mission. He records it as SOE Denmark Tablejam 342, flight time 7 hours.

My Grandfather Arthur Johnson flew Halifax LL353 ‘L’ and towed a Hamilcar on D-Day.

Thanks Gaynor. As you probably already know, your Grandfather (298 Squadron) towed Hamilcar 245, which was piloted by S/Sgt Desbors and was carrying 3 Rota trailers for LZ N in Operation Mallard.

Hi. Do you have similar details for Operation Varsity? My father’s plane towed Horsa chalk 238, probably carrying 6lb anti-tank gun from the 4th Air Landing Brigade. I do not know who the Horsa pilot was, or if he survived.

Hi Martin

I’m not an expert on Varsity, but Steve Wright is. He is the author of a book about the operation, ‘The Last Drop’. You may get an answer from him if you post your query on the Glider Pilot Regiment Public Group on Facebook.

Ah yes, I have Steve’s book and met him at the GPR service in 22. I think this one must be lost in time though. I did once find possible names for the gun crew they were carrying but nothing for the pilot(s).

Thanks for all the work you’re putting in to keep these memories alive.

Hi Martin

My father was one of the Co-Pilots on Horsa Chalk 238.

According the army flying museum the two pilots were Sergeant Hyland and Flying Officer Duke. The pilot of the Halifax was Flying Officer Blair. Is that your father?

My father Flying Officer Duke survived but I dont know what happened to Sergeant Hyland

I look forward to hearing from you. Ian Duke

Oh, that’s excellent! My father was the Air Bomber in Blair’s crew. It was only their second mission. My mother said that he had nightmares about it, and I suspect he never knew what happened to the men they had towed.

Hi Ian, this article is really interesting as it gives me a glimpse into the flights undertaken by my late grandfather, Leonard Cooke. He was a rear gunner on 298 Sqn and took part in Op Varsity, flying in ‘N’, just one hull letter out from Ray’s ‘M’. I have Leonard’s log book details and he also flew in ‘J’, seen in your photo of the three Halifaxes. He could also be milling about in front of the aircraft! Leonard also flew on ‘Crop 29’ on 29 April 1945, during which the Halifax now in Canada was shot down. I also became RAF rearcrew (on helicopters) and helped to undersling a Hercules engine from Isla (a Beaufighter crash site) to Machrahanish, to help with the restoration. A precious article indeed, thanks for recording it.

Thanks Richard

My Grandfather was the Engineer Paddy Creane. I wonder if any of the Squadron families have any crew photographs that would be so important?

… should have said, I never knew him so photos and information about ‘him’ are so important and now so very rare. Thank you for this information page.

Thanks. I’ve added a photo after the Raid Report above. Unfortunately it’s very poor quality, but the original has been lost.