If you like undiluted collections of veterans’ accounts of airborne operations, this book is for you. If however you prefer your history with, well, a bit of history, then you could find this book frustrating.

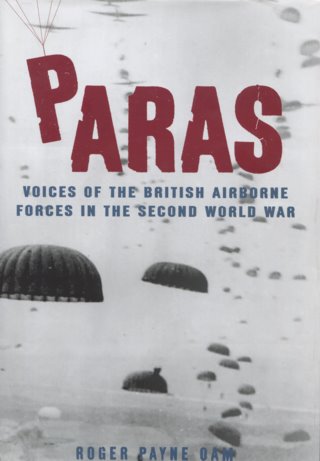

Review of ‘PARAS – Voices of the British Airborne Forces in the Second World War’ ed. Roger Payne, published 2014 by Amberley.

Review of ‘PARAS – Voices of the British Airborne Forces in the Second World War’ ed. Roger Payne, published 2014 by Amberley.

[This review is based on the hardback edition and focuses primarily on the Sicily accounts in the book.]

There is no doubt that the accounts of veterans of WW2 are historically extremely valuable (for examples of outstanding book-length accounts, see Peter Davis’ ‘SAS: Men in the Making’, and Victor Miller’s ‘Nothing is Impossible’). There is also no doubt that we owe our veterans our undying gratitude and respect. But just because a narrator was an eye-witness does not make his version gospel, and the rule of the fog of war usually meant that individuals often did not see the bigger picture. For these reasons alone, personal testimony deserves as much careful editing as any other kind of history, and not just of the raw text. In this book, however, multiple accounts of variable quality stand alone.

‘PARAS Voices of the British Airborne’ consists almost entirely of short accounts by veterans of Britain’s airborne divisions in WW2, many of them excellent. Despite the title, however, not all of these men were paras. Glider pilots feature, as well glider troops, and some of them objected to being lumped together with parachutists by the press. The soldiers of the glider battalions were not taught to parachute, and many resented having their (arguably even more dangerous) method of arriving on the battlefield overlooked.

One problem with the book is that you often cannot tell quite who an account is by. Yes, a name is given at the start of every account, but usually not the unit the man belonged to, nor his rank, nor the where, when, and why of the story. In these cases you have to work all this out by yourself from the contents of the account, and sometimes you cannot. This seems to be taking the primacy of the verbatim voice of the veteran too far. Sometimes you cannot even tell if the section is by a historian or a veteran. The first section, which looks like all the others, is in fact by the editor, which makes you question later sections.

As regards Operation Ladbroke, the massed glider assault on Syracuse that began Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, there are only six accounts, amounting to about 3% of the book’s total text. Three accounts are about gliders in the sea, and, of these, two are available in similar versions online at the Pegasus Archive and BBC People’s War. One of the six accounts is by Jim Wallwork (of Pegasus Bridge fame) whose story is already well known, and another sounds as if the man was in Wallwork’s glider. Finally there is one account that is apparently second hand, i.e. by somebody who was not in the action of the story, but reporting what happened to a mate (another already published story).

Regarding the later parachute attack on the Primosole Bridge near Catania in Sicily, there are two (possibly four) accounts by British veterans and one interesting letter from a German soldier. The two ‘possible’ accounts might be about the Primosole drop, but, for reasons given above, it is hard to tell.

The bulk of the book is taken up with training, Tunisia, Normandy, Arnhem and the Rhine.

There are some excellent accounts in this book, but they are let down, particularly from the point of view of a historian, by the lack of context and editing. There is no contents page and no index (so it’s hard to return to an account you remember). The accounts are not strictly chronological within their chapters, so, for example, Tunisia and Sicily accounts are intermixed. There are no footnotes, and no bibliography or sources. The last would be welcome even if only saying “unpublished manuscript”, “interview with editor” or similar. Given these lacks, it is no surprise that there are no maps. It would not have taken much effort, and surely it would not have degraded the veteran’s authentic voice, to give his rank and unit (e.g. South Staffords or Border), and to briefly set the scene for the action he was taking part in.

It could also have been useful to edit out the more obvious mistakes by some veterans, such as mixing up the Ponte Grande, Primosole and Pegasus bridges, substituting Germans for Italians, labelling 5 Division as 5 Corps, or attributing Lieutenant Colonel Walch’s leadership to Colonel Jones. Admittedly such correcting or interpreting work would have taken a lot of effort, and times are hard enough in publishing already. It could also have resulted in distraction from the verbatim account, and maybe even give offence to the veterans or their families. As things stand however, not only might you sometimes struggle to work out precisely what is happening, you may also feel you cannot trust some of what you are reading, and this undermines and distracts.

All this said, some of the pieces in the book are outstanding, and it does provide a very large collection of accounts, many (most?) apparently not previously published. If that is what you like, or you are a fan of the bare-text “voices” trend in publishing, then this is a book well worth buying.

The paperback on Amberley’s website: here