Gunners without guns, an LZ without defenders, impenetrable fog – the British glider assault in the invasion of the South of France went seriously awry.

Operation Dragoon was the code name for the Allied invasion of the South of France in the summer of 1944. But before it was Operation Dragoon, it was Operation Anvil. Anvil was originally planned to take place in conjunction with Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy. According to Field Marshal Alexander, Overlord was to be the hammer in the north of France that smashed the Germans against the anvil in the south. Lack of landing craft meant that Anvil in June became impossible, much to Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s delight.

He had been opposing Anvil from the start, preferring an invasion of the Balkans. Eventually the exasperated Americans ganged up on him and he submitted. There’s a story that Anvil became Dragoon because Churchill felt he had been dragooned into it. So the invasion of the South of France eventually did go ahead, although not in conjunction with D-Day the 6th of June in Normandy. Instead, D-Day in the south ended up being set for the 15th of August 1944.

By invading the South of France the Allies hoped to gain more ports (Toulon and Marseilles) and to put pressure on the Germans’ southern flank. The plan was to land three divisions by sea between Cannes and Toulon. Airborne forces were to be dropped further inland to block German counter-attacks.

It was for exactly this kind of eventuality that a squadron of the Glider Pilot Regiment had been kept behind in the Mediterranean when the 1st Battalion returned to England in 1943 after the invasions of Sicily and Italy. Christened the Independent Squadron, it was formed from the 3rd Squadron. By the time of Operation Dragoon, it was more formally titled the 1st Independent Glider Pilot Squadron.

Sgt Will Morrison, one of its pilots, characterised it as the ‘heavy’ (i.e. Horsa) squadron of the Battalion. Many of its pilots had participated in Operation Beggar, fetching Horsas from the UK to North Africa for the invasion of Sicily. At the time, the rest of the Battalion had been flying the smaller American Waco glider.

At first the newly formed Squadron was sent to the Allied Airborne Training Centre, initially at Oujda in Morocco, then at Comiso in Sicily. Ironically, here the Horsa pilots trained not in Horsas, but in Wacos, with a liberal allocation of flying hours. Even more ironically, as the Squadron began to ferry in and receive Horsas for Operation Dragoon, training hours dwindled to almost nothing.

In July 1944 the Squadron moved to mainland Italy, eventually ending up at Tarquinia, one of several airfields near Rome which were being set aside for the airborne forces that were assembling for Dragoon.

A temporary, ad hoc selection of airborne units had been put together just for the invasion. Roughly equivalent to a division in strength, it comprised both American and British units. It was named the 1st Airborne Task Force (1ATF). A temporary grouping of Troop Carrier aircraft units was also assembled, under the title of the Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division (PTCAD). It consisted of C-47 (Dakota) aircraft in the American 50th, 51st and 53rd Troop Carrier Wings.

Four separate airborne landings were scheduled for 15th August:

- Operation Albatross, a dawn mass drop by paratroopers at about 5am

- Operation Bluebird, a glider landing at about 8am

- Operation Canary, a reinforcement drop of paratroopers at about 6pm

- Operation Dove, a mass landing by gliders immediately following Canary

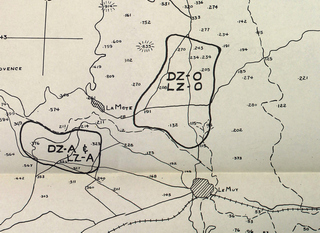

The area chosen for the landings was around the critical crossroads town of Le Muy, some nine miles from the coast. Three drop zones (DZs) were chosen near Le Muy for the drops by parachute troops. Two of them also doubled as landing zones (LZs) for gliders. The British troops were due to land in DZ / LZ O. It was in a valley about a mile wide and two miles long north of Le Muy. It consisted of a patchwork of fields and vineyards interspersed with hedges and trees. The hamlet of Le Mitan, inside the LZ, was chosen as the site of the British and 1ATF Headquarters (HQs).

The British element in 1ATF was the 2nd Parachute Brigade Group. It was due to drop on DZ O as part of Operation Albatross, while American paratroopers dropped on DZs A and C. The American units included air-dropped artillery. This consisted of 75mm Pack Howitzers which were broken down into several separate parachute loads. British doctrine was against parachute-dropped artillery, so 2nd Parachute Brigade’s artillery would have to be delivered by glider.

Operation Bluebird

This glider landing of the British artillery units was called Operation Bluebird. It was timed to arrive a few hours after the dawn parachute drop, so that the paratroopers would have time to consolidate their hold on the LZ before the vulnerable gliders came in.

There were two groups of aircraft taking part in Operation Bluebird.

The first group comprised 35 Horsas piloted by the British glider pilots (GPs) of 1st Independent Squadron. The Horsas were to be towed by C-47s of the American 435th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) based at Tarquinia. The Horsas carried jeeps and guns of two British airborne artillery units. One was the 64th Air Landing Light Battery RA equipped with 75mm Pack Howitzers. The other was the 300th Air Landing Anti-Tank Battery RA armed with 6 pounder anti-tank guns.

The second group in Operation Bluebird consisted of 40 Waco gliders piloted by American GPs, towed by C-47s of the American 436th TCG. 26 of the Wacos carried British artillerymen of 64th Light Battery without their howitzers, which were in the Horsas. The other 14 Wacos carried the US 512th Airborne Signal Company, and parts of 1ATF HQ. The HQ was due to be located at Le Mitan in LZ O.

The first of the Horsas of the Independent Squadron took off at 5:19am from Tarquinia. The Squadron was commanded by Major Coulthard, and divided into three flights under Captains Turner, Mockeridge and Masson. These four men now commanded echelons each comprising a quarter of the Horsas. The group finished assembling above the base and set off at 6am. Meanwhile the first of the Wacos took off at about 5:30am from Voltone, not far from Tarquinia. There were immediately a couple of problems.

One of the Wacos had a tow rope break shortly after take-off, and it ditched in the sea about five miles off the coast. The American signallers on board shared a bottle of whisky while they waited for rescue. The men were soon picked up by boat and reassigned to a later lift. The glider was towed back to shore.

Also shortly after take-off, one of the tugs developed engine trouble and released its Waco back onto the airfield. A substitute tug was found, and the lone combination later took off and headed for France on its own.

Once assembled, the rest of the Waco group set out, about eight minutes behind the Horsas. The route from Italy to France looked easy on the map. The islands of Corsica and Elba both have fingers of land at their northern ends, and the route ran past the tips in a completely straight line. But the planners were taking no chances. Lessons had been learned from the disastrous over-water approaches during the invasion of Sicily a year before.

Now there were radio beacon ships and rescue vessels all along the route, and navigational aids such as Gee and ground-scanning radar were in use. Pathfinders had been dropped on LZ O to set up fluorescent and smoke markers, as well as Eureka homing beacons. The route ran alongside, rather than over, the Allied assault ships, with their nervous anti-aircraft gunners. What could go wrong?

The Fog of War

The answer, of course, as so often with airborne operations, was the weather. The two groups of Operation Bluebird had passed Corsica when the leading tugs received a signal from PTCAD back in Italy. The LZ in France was shrouded in thick mist and landing the gliders safely was impossible. The Horsa group was ordered to return to Italy. C-47s could only tow the large and heavy Horsas with difficulty, and the strain consumed fuel at an alarming rate. There was not enough fuel for them to loiter and wait for the fog to burn off. So the 435th TCG, towing the Horsas, turned 180 degrees and headed back to Tarquinia.

The Waco group being towed by the 436th TCG had no such problem. The smaller, lighter Wacos did not strain the C-47s. The group circled near Corsica, waiting. Already short of two Wacos due to the mishaps just after take-off, the group suffered a harrowing accident when the right wing of a Waco fell off, rolling it over and snapping the tow rope. The glider then disintegrated, tipping the GPs and passengers into the sea far below. The tug circled above the wreckage until Air-Sea Rescue arrived, but, inevitably, there were no survivors.

While the Waco group circled near France, the Horsa group reached its base at Tarquinia in Italy at 8:40am. On the way back it had lost two Horsas when their tugs ran low on fuel and released them. Both gliders landed safely at an airfield on Corsica.

The Horsa group had also encountered the lone Waco and its substitute tug coming the other way, still headed for France. Thinking that the whole operation must have been scrubbed, the Waco tug pilot turned about and unwittingly followed the Horsas.

Equally unwitting, after landing back at base in Italy, was the crew of a jeep in one of the Horsas. The story goes that they thought they had landed in France, and they were keen to drive out of the back of the glider into action, wrecking it in the process. They could only be restrained with difficulty. (This sounds like a tall tale told after dinner in the mess, or “shooting a line”, as GPs of the time would have called it.)

It was quickly decided that the Horsa group should head back to France later in the day, at the front of Operation Dove with its many hundreds of aircraft. Horsas were hurriedly fetched from wherever they had landed on the airfield. All the aircraft were remarshalled, the tow-ropes laboriously laid out again and everything checked and rechecked.

Waco Group

Meanwhile, near France, the Waco group had circled for about an hour. Finally the morning mist cleared and the group headed inland towards LZ O. To everybody’s surprise, there was no warm welcome from German anti-aircraft guns. A bigger surprise for the GPs as they glided down was the sight of anti-glider poles all over the LZ, which they had not been told about (though sources differ on this).

The British pathfinders and parachute engineers already on the ground had been working frantically to take down as many poles as they could, but by the time the Wacos started landing at about 9:30am there were still plenty left. A photograph of the Wacos landing at the north end of LZ O (left) shows no signs of impacts to their wings, so perhaps the paras had succeeded in that sector. However, later photographs of other fields show poles still standing, and there were many crashes and bad landings due to the difficult terrain and the obstacles.

Despite this, it seems the gunners of 64th Light Battery arrived comparatively intact. Only one man was killed on landing, when his Waco turned upside down (two had already been killed when the Waco disintegrated over the sea). 13 men were wounded in crashes, although eight of them soon returned to duty. One of the injured was the CO, so the 2 i/c, Captain Martin, took over.

Without their howitzers, which were still in the Horsas back in Italy, the gunners could not fulfil their role, so Martin deployed them in infantry positions. Reporting to the HQ at Le Mitan, Martin met an American major who said he knew where some guns could be found. He sent a scout with Martin, and by the middle of the afternoon four guns had been brought in. (It is not known whose guns these were, but Martin was explicit that they were not the 64th’s.)

The Bluebird Wacos may not have brought the 64th’s guns, but they had a different kind of impact on some Germans who were holding out in a farm in the LZ. A parachute battalion war diary explained: “the sight of the gliders bringing in reinforcements was too much for the Germans, and acting on [a British sergeant’s] suggestion the whole force of eighty odd men laid down their arms and surrendered to him, handing over 48,000 francs from the canteen.”

Preparing the Ground

Meanwhile efforts continued to prepare LZ O for the arrival of the Bluebird Horsa group and the Wacos of Operation Dove. Scheduled for late afternoon, Dove comprised 335 gliders, piloted by American GPs, and carrying an American glider infantry battalion, along with other units, vehicles and tons of supplies. It was vital to clear as much space as possible to avoid unnecessary crashes and casualties. Captain Martin sent some jeeps to help the pathfinders and the engineers in pulling down glider poles.

However, it was not just poles and trees that threatened the incoming gliders – the already-landed Wacos from Bluebird posed almost as great a hazard, in what was to become a massively overcrowded LZ. Parties of men began manhandling the empty gliders across the fields and parking them in a line against the nearest hedgerow, out of the way. Through the day the crack of explosives could be heard as others were blown up and burned, leaving the shadowy shapes of Wacos smudged in black ash on the ground.

While this was going on, the men of the British 2nd Parachute Brigade were trying to follow their Phase 1 orders, which were to hold the LZ, to block the bottle-neck roads against German counter-attack, and to dominate Le Muy. In Phase 2, they were supposed to attack the town. However, thanks to the fog many sticks of paratroops had gone astray, particularly from the 5th Battalion, who were due to guard the north side of the LZ.

Captain Martin was alarmed to find nobody there, precisely where the Horsas carrying his 75mm howitzers were due to land. Without enough men, there was little the commanders at HQ in Le Mitan could do about it, and, apart from patrols, they kept the remnants of the 5th, along with Martin’s handful of scrounged 75s, to defend the hamlet.

The British paras did not attack Le Muy, perhaps partly because of the lack of artillery support. Of course, it wasn’t just the 64th’s howitzers that were missing. All the 6 pounder anti-tank guns of the 300th Anti-Tank Battery were also absent. The original plan was to parcel them out among the three para battalions, to proof their roadblocks against enemy armour. Without them, if the Germans had attacked with tanks down the road from the north, there would have been nothing to stop them overrunning Bluebird’s landing fields. Luckily, no such attack materialised.

Back in Italy the Horsa group started taking off again for France in the middle of the afternoon. To make up for the two gliders that had landed in Corsica, two substitutes were provided from reserves, bringing the total back to 35. En route however the group was joined by one of the Corsica Horsas, making 36 (the remaining Corsica Horsa flew into France the next day, bringing the final total to 37). The lone Waco from the morning’s aborted take-off also tagged along.

Massed Gliders

Behind the Horsas streamed the 700 or so aircraft of Operations Canary and Dove. They were escorted by 54 P-51 Mustangs liveried in silver and red, with black and yellow chequered tails. The harlequin fighters zipped around and between the troop carrier formations at speeds that made the lumbering C-47s seem to be hardly moving. To the relief of the tug and glider crews, but possibly to the disappointment of the fighter pilots, the Luftwaffe did not make an appearance.

The journey was uneventful, although some ineffective fire was directed at the Horsas as they approached LZ O. They headed for the north end of the LZ, aiming for fields next to those where most of Bluebird’s Wacos had landed in the morning.

Photographs of the LZ show many good landings in open fields, even those where there were anti-glider poles still standing. It seems the massive wings of the Horsas smashed through them. Other gliders landed among the trellises of the vineyards, losing their nose wheels in the process. At least four Horsas overshot, including the lead glider flown by Major Coulthard, which burst through the boundary trees. Photographs also show one Horsa landing very heavily, apparently bouncing before stopping in a cloud of dust.

The British troops emerged from the gliders and began removing the Horsas’ tails to extract the guns and jeeps. Other gliders had their tails high in the air, and the crews opened the forward side doors instead. Soon all the men were running for cover as the sky filled with hundreds of Wacos coming in to land. The gliders of Operation Dove had arrived. Due to various mishaps, the squadrons had bunched, and Wacos were simultaneously descending from many different heights and many different directions.

LZ O rapidly began to fill with careening and crashing Wacos, leaving few spaces for those still gliding in. Pilots frantically watched for other gliders coming at them from any direction, while co-pilots equally frantically looked for a vacant spot to aim for. Gliders competed for open spaces, funnelling in dangerously close to each other, speeding up to land quickly, then landing too fast.

Left: Sgt Roy Jenner, a photo inscribed to Bert Patton, “my pal”. Right: Sgt Albert Patton. Source: Robert Patton

Being Alive and Well

The Horsas had been lucky to be at the head of all the gliders, and, apart from some of the morning’s left-over Wacos, they had the LZ all to themselves. Nevertheless, nine British GPs became casualties – two officers and seven sergeants. Six of the nine were seriously wounded and ended up in hospital in Naples. The two wounded officers were the CO, Major Coulthard, who broke both legs, and Lt Hain, 2 i/c of No. 1 Flight, who broke his back when he ended up underneath the jeep he was carrying. The only fatality was Sgt Roy Jenner.

Sources differ as to what happened to Jenner. One says he was hit by a German gun as he was landing, and then crashed on top of it. Another says he was hit by artillery fire. Yet another says he flew into a tree. The same source says he died that day, although CWGC records give the date of his death as the 19th. Sgt Albert Patton, who flew with Jenner, made no mention of artillery, and recorded in his log book simply: “very heavy crash – Sgt Jenner killed”.

Despite the rough landings and casualties, most of the cargos of guns and jeeps were undamaged, even if it took a while to extract some of them from the Horsas. By the end of the day, 300th Battery had 14 of its 6 pounders available, and 64th Battery had eight of its own 75s. The British GPs may have brought their charges late to the battlefield, but their efforts were not entirely wasted.

Later that night the 64th supported an attack by an American glider infantry regiment against Le Muy, although the darkness meant observed and adjusted fire was not possible. The attack failed. British gunners had better luck the next day, when a 6 pounder gun fired four anti-tank and 21 high explosive shells at a house in Le Muy that the Germans had used as a strongpoint to thwart the night attack. This time the Americans captured the town.

The Allies were very complimentary about each other. Captain Martin of the 64th described the cooperation he got from American troops as “100%”, while a report by the American 76th TC Squadron noted: “Towing a Horsa is no mean feat, particularly in formation … however … all of our pilots commented on the ‘smoothness’ of the British glider pilots in their handling of the bulky ‘Horsas’. This made the task of the tow planes far easier than it would otherwise have been.”

At the end of D-Day, the British GPs, who had hardly slept the night before, and who had wrestled their “bulky Horsas” for an unexpected seven hours, felt the exhaustion of a very long day fuelled mainly by adrenaline, even though there had been no combat. Suddenly life’s small pleasures seemed more precious. Sgt Morrison (in his book “Horsa Squadron”) later recalled savouring a gourmet meal concocted from British and American rations by Sgt Bert Patton. The distraught Patton had been chosen to be duty chef by his mates, perhaps to help take his mind off having survived the crash that killed Jenner, his best friend. Being alive and well, Morrison mused, was almost sufficient.

.

This article first appeared in Glider Pilot’s Notes, the magazine of the Glider Pilot Regiment Society.

US National Archives images and help with original US Troop Carrier Command documents courtesy of the Leon B Spencer Research Team of the US National WWII Glider Pilots Committee.

Sgt Will Morrison is my Grandad. Forever proud xx

I have a copy of your grandad’s book. My father spent all his post war career working overseas in the pre email world when communications were very much more difficult than they are now. He attended squadron reunions whenever he could and was very proud of the men under his command.

I have posted photos in the GPR Public Group on Facebook.

Best wishes,

Gavin Coulthard.

Sgt Roy Jenner was my Grandma’s husband, nice to see a picture of him and hear about the Operation. Thank you