Glider Z only flew in Operation Ladbroke because a senior officer wangled an extra tug plane. More than one commentator thought he had no business being there.

Glider: CG4-A Waco Z, serial no. 277185.

Glider carrying: Senior airborne officer and staff, plus 10 men of Simforce, 2 South Staffords.

Troops’ objective: The Ponte Grande bridge.

Manifest

From 2 South Staffords, 1 Air Landing Brigade (1 ALB), 1 Airborne Division (1 AD):

Lieut Reynolds.

C/S Bluff.

Cpl Hutton.

L/Cpl Insley.

2 Nursing Orderlies.

Pte Cashmore.

1 Driver.

2 O.Rs. F Coy.

Plus Lt Col A G Walch and from two to five of his staff.

One of the NOs was Private F J Back of 181 Field Ambulance.

Glider Z was a last minute addition to the glider force in Operation Ladbroke, the opening attack in Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in 1943. It was included because Lt Col A G Walch wanted to take part.

Walch was one of the founding fathers of the British airborne forces, along with Maj Gen Frederick Browning. Both men had been involved in setting up 1 Airborne Division (1 AD), but neither of them was technically a part of the division any longer. Browning had been appointed to be the primary adviser on airborne matters to Gen Eisenhower, the Allied Commander in Chief. Browning had taken Walch with him as his Chief of Staff.

This meant of course that Walch had tremendous clout when it came to getting what he wanted. In this case he decided he wanted to fly with the men of 1 ALB and witness the fighting at first hand. He classed himself as an ‘spectator’, which in theory meant he would not be part of the chain of command in the battle. We do not know how many aides or others of his staff he took with him, but it would have been from two to five, depending on whether extra seats had been added to the glider.

Whichever number it was, we know that it left ten seats free for fighting troops. These were allocated to men in a scratch force of Staffords under Lt Simonds, which was christened Simforce. It was not part of the standard Staffords rifle companies, and was styled as a Battalion Reserve. Simforce was spread across two other gliders besides Z: gliders 53a and 54a. Both landed in the sea, leaving Reynolds’ detachment as the only representatives of Simforce to take part in the fighting.

The tug plane that towed Glider Z was Browning’s own personal C-47. Not that Browning totally lost out on the excitement. While his borrowed C-47 was towing Walch to Sicily in Glider Z, Browning himself was also in the air over the battlefield. He was a passenger in a Beaufighter night fighter flying over the LZs and DZs, also, like Walch, an ‘observer’.

Like many senior officers, Browning and Walch did not want to miss the action. Some other senior officers thought that men at their level should not be risking themselves at the front. More than one (including Browning himself) commented that Walch in particular “had no business being there”.

Glider Pilot’s Report

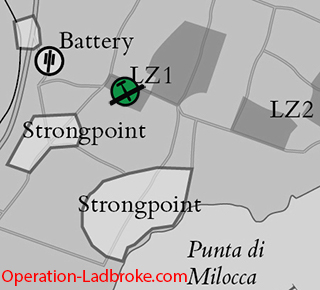

Glider allotted Landing Zone: LZ 1.

First Glider Pilot: Staff Sergeant Turnbull, R

Second Glider Pilot: Staff Sergeant Coulson

“Good but bumpy tow, intercomn went u/s on take-off. Glider released at 2300 hrs at 2000 ft over PUNTA DI MILOCCA and landed in cactus hedge about one mile N. of L.Z. No casualties.”

The GP did himself a disservice by saying he missed the LZ by a mile. In fact Glider Z made one of the best landings of the night, actually landing intact within the boundaries of its target LZ, LZ 1 [map]. This was a feat achieved by only four other gliders, according to aerial photographs. Out of a planned 144 gliders, this puts Glider Z in an elite group of just 3.5%.

It was also an unusual landing in that Glider Z came in from the west. If it really was released at 2000′ directly over Milocca Point, then it had plenty of height in hand, and presumably flew further inland and turned.

With a 35 mph wind behind it, the landing must have been a fast one. The glider clipped some electricity cables with the top of its tail, pulling down the posts, and then ploughed through a hedge of prickly pear cactuses. It was examined later, after the battle:

“Struck power lines and landed through cactus hedge. Top of rudder and vertical fin apparently damaged through contact with power line while flying under them. Under portion of nose smashed by cactus hedge. Right landing gear and struts damaged.”

Walch wrote:

“The flight in the gliders really was uncomfortable. Conditions were very bumpy indeed and the noise of the wind buffeting the thin fabric sides made shouting necessary even when talking to one’s neighbour; the gliders bounced and jerked at the end of the tow-rope and nearly everyone was very sick indeed. The physical strain on the glider pilots was considerable and they could not relax for one moment.

The glider pilots chose to land on a wall inside the Italian defensive position at 118246 at about 2245 hrs; the impact was sharp but the only casualty was a broken arm caused by a loose rifle flying down the aisle of the glider. The Italians in trenches within yards of the glider were surprised and took no action.”

Photographs show that Walch was mistaken about landing inside the strongpoint at 118246, which consisted of pillboxes and was surrounded by dense barbed wire. It later put up a fight against attacking seaborne troops. Of course the real reason why Walch and his staff were not molested was that they actually landed further north in LZ 1, which did not have Italian trenches in it.

Tug Pilots’ Report

Tug: C-47, “Boy’s Boys”, serial no. 41-38695, HQ Sqn Troop Carrier Command USAAF.

Takeoff: c. 18:54 from Airstrip A, El Djem Base, Tunisia. Priority 29, element of one.

Pilot: Capt Beck, Joe A

Copilot: 2 Lt Thatcher?, Neville

Navigator: 2 Lt Denny, George P

Engineer: S/Sgt Smith, Gordon B

Radio Operator: Sgt Starkowski?, Theodore A

“5 SL [searchlights] on peninsula, light & heavy AA on coast.

Hit Rel Point?: Yes

Time of Release: 2257

Altitude: 2200

Vary from Course: No”

The time of release clashes with Walch, who says the glider landed at 22:25.

Joe Beck was an experienced pilot, who had helped train airborne troops at the Central Landing Establishment at Ringway in England. He had then dropped paratroopers during Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942, during which he was shot down by four Vichy French fighters. He survived and joined the HQ Squadron of Troop Carrier Command (TCC) at Algiers in early 1943. Here he ferried senior Allied officers, including Maj Gen Hopkinson, CO of 1 AD. While doing this he met Maj Gen ‘Boy’ Browning, who was the chief Airborne Adviser at Allied Forces HQ (AFHQ). Browning adopted Beck, his crew and his C-47 as his own personal transport aircraft. It was in honour of this selection that the name of the plane became “Boy’s Boys”.

George Denny, Beck’s navigator, was also well-connected. He was the nephew of W Tudor Gardiner, the Assistant Chief of Staff of 51 Wing TCC, which provided most of the tug planes for Operation Ladbroke.

“Boy’s Boys” was tacked onto the rear of 60 Troop Carrier Group, and unlike the other tugs, which flew in formations of four, sharing a single navigator, it was scheduled to fly alone, which must have eased matters considerably.

Both Beck and Denny left accounts of their role in Operation Ladbroke in Charles Young’s book about the TCC, ‘Into the Valley’.

Walch wrote:

“The tug pilots, determined to release so that the glider had every chance, spent a long time flying about inland checking their position.”

Oddly, neither Denny nor Beck mention this.

The Way to Waterloo

After landing and presumably wondering for a while where they were, the men prepared to move on to the Ponte Grande bridge (codenamed Waterloo) [map]. Walch chose a circuitous route, to avoid Italian strongpoints. Being his own man, and not under 1 ALB orders, he was wise to choose the round-about route he did, as he and his men arrived at the bridge without casualties.

Many years later, the Imperial War Museum’s production company recorded an interview with Jack Reynolds, the senior officer of Simforce in Glider Z (you can listen to it [here]). Reynolds said that he argued with Walch about which way to go, as he was under orders to take a different route. Walch was greatly senior to Reynolds, but officially only an observer, so Reynolds ignored him, and took his men the way he wanted to. They were not as lucky as Walch’s party. According to Reynold’s citation for the award of an MC for his part in Operation Ladbroke:

“He led his party throughout the night to Waterloo Bridge encountering stiff opposition on the way during which six of his nine men became casualties. On the way he collected several stragglers, forming them into an organised group, eventually assisting in the defence of the Bridge, during which two more of his men were killed and another missing.”

Pvt Back, one of the nursing orderlies, was killed by machine gun fire shortly after the landing, and is buried in Syracuse Cemetery, as is L/Cpl Insley (although recorded as a Private). None of the other named men in Glider Z are buried there, so perhaps the other four casualties (of the six mentioned) were only wounded.

Meanwhile Walch found the night puzzlingly quiet and empty. Where were the hundreds of airborne troops that should have been fighting nearby? Unknown to Walch, most of them were either miles away, or had landed in the sea. Setting off with his ‘very “amateur” party’, he skirted the gun battery Mosquito (for an explanation of the Italian defences and their codenames, see [here]). They then met a group of about 30 glider troops on a back road and joined them. Still trying to avoid the enemy, they eventually arrived near strongpoint Walsall at 04:40.

At the Ponte Grande

In his report Walch speaks of himself in the third person:

Lt Col Walch decided to take his party straight on to the bridge without tackling the Italian post now firing at them from 123285 [strongpoint Walsall]. They arrived at the Ponte Grande at about 0500 hrs without trouble, although fire from enemy MGs at 134282 [battery Gnat] was falling just short while they were crossing the open ground just to the south.

Lt Col Walch now found himself to be the senior officer at the bridge and so took command. […] At 0630hrs Lts Deucher and Reynolds with a mixed party of about 23 ORs arrived at the bridge, to increase the total airborne strength there to about 7 officers and 80 ORs […]

At 0800 hrs the bridge and forward positions came under heavy and accurate mortar fire from the west and north […] Within the next hour all the defending troops were withdrawn into positions on the canal; Lt Welch and 2 sections [including Reynolds] were on the east side of the bridge and the remainder of the force on the west. Until 1200 hrs the LMGs kept the enemy at a distance while the remainder of the party rested […]

By 1445 hrs all the outlying defence posts were wiped out and half-an-hour later the remaining unwounded defenders were cornered at the point where the canal joins the sea. There was no cover whatsoever, only a few rounds of ammunition left, and at 1530 hrs most of the force was overrun by the Italians […] Only three quarters of an hour later, at 1615 hrs, 2 RSF of 17 Infantry Brigade arrived, recaptured the bridge still intact, and were joined by Lt Welch and his party of 7.

In the meantime, Lt Col Walch and the rest of his force [including Reynolds], as prisoners, were marched west for about 45 minutes, picking up other airborne prisoners on the way, until a patrol of 17 Infantry Brigade came in sight. They then escaped from their captors, obtained permission from Brigadier G W Tarleton commanding 17 Brigade to return to the Ponte Grande and by 2100 hrs had again taken over its defence – armed with captured Italian weapons.

Walch may have had no business being there, but perhaps it was just as well he was. Not one of the division, brigade or battalion HQ detachments had arrived. This made Walch and his staff a kind of default divisional HQ, even though there was not much for such an HQ to do. Nevertheless, perhaps he felt obliged to take command. And although some may have later carped at his presence, none of them criticised his performance.

Quotations from Walch’s account by kind permission of The Airborne Assault Archives.

With thanks to Steve Bluff for the photo of his father.

Hello,

Fantastic article – I wondered if you might be able to shed light on the source for the manifest for this glider Z? Fascinated to see certain names listed and I wondered if this was the case for other gliders?

Andy

Thanks. The loading table comes from the Staffords war diary, WO 169/10299 in the National Archives. Few entries have names. The Staffords archive at Whittington Barracks probably have a copy. It also appears in ‘By Land, Sea & Air’ p174.