The cliffs below the gun battery at Cape Murro di Porco are daunting. Did Major Paddy Mayne’s SAS Special Raiding Squadron really climb them to attack and destroy the guns? Recently discovered documents shed new light.

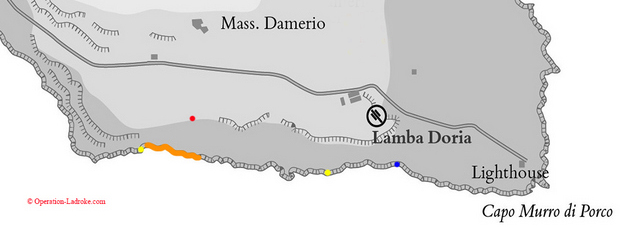

The southern coast of the Maddalena Peninsula south of Syracuse in Sicily is rocky along its entire length [map]. At its western end, near an area called Terrauzza, there is a flat rocky beach [story], suitable for landing from the sea. At its eastern end, however, near a headland called Cape Murro di Porco, the cliffs look unclimbable. They are sheer, 15 to 20 meters tall and often undercut.

Between the cape and the distant beach at Terrauzza, the vertical cliffs alternate with sections where the rocks are at water level, or close to it. In these places the rocky ground then ascends in stepped layers or steep bluffs towards the spine of the peninsula.

Today, the ruins of a WW2 gun battery still lie among the rocky outcrops above the cliffs near the cape. The battery [map] is called Lamba Doria, after an Italian naval hero. It is only some 200 to 300 meters from the cliff edge. It is here that the cliffs look most unclimbable. Yet people tend to assume that the men of Britain’s elite SAS Special Raiding Squadron (SRS) climbed these cliffs in the darkness of 9/10 July 1943 to attack and destroy the guns. But did they really? There was a more accessible place, a gap in the vertical cliffs, not far away. Surely, the planners of the operation would have chosen the easier landing.

These Men Are Dangerous

The presumption that the whole of the SRS heroically climbed almost unclimbable cliffs at night in Sicily probably arises from one of the first books to tell the tale. In 1957, a mere dozen years after the end of the war, “These Men Are Dangerous” by Derrick Harrison was published. Harrison had been the Lieutenant in charge of C Section of 2 Troop of the SRS in Sicily. The book is an invaluable record, and a good read. However, as was fashionable at the time (and indeed probably preferred by publishers), it is written in parts in the style of an action novel. One of those parts concerns climbing the cliffs.

The cliff climb Harrison describes is fraught, the language overwrought: “We had been edging our way along a ledge of rock for some minutes when … the ledge was not there any more. I remember thinking only that I must try another way. I could see nothing. It was as if someone else were guiding my hands and feet.” This dramatic style would make the story perfect for weekly serialisation, in this case complete with, literally, a cliff-hanger. “How long that climb took I do not know. It could have been ten minutes or ten years.”

The lack of specifics is brilliant, as it leaves the reader free to imagine the most horrific of cliff faces. No mention is made of ropes or ladders, although the men were heavily loaded with weapons and ammunition. A year later in Normandy, American Rangers assaulting the 30m vertical cliffs at Pointe du Hoc used ropes on grapnel hooks launched by rockets, as well as fireman’s ladders. So how vertical can Harrison’s cliffs have been? No mention is made of overhangs or undercuts, which rules out much of the worst of the cliffs at the cape.

Harrison says his job was to escort the SAS engineers who were supposed to destroy the guns, and make sure they reached the battery safely. One of those engineers was Sgt Bill Deakins. He wrote an account of his time with the SAS in his book, “The Lame One”, published in 2001, nearly 60 years after the invasion of Sicily. The title of the book refers to a problem that Deakins had with his spine after being hit by a truck. The problem was not enough to disqualify him from the SAS, although he was excused parachute training. Perhaps his condition would have also excused him from climbing vertical cliffs.

Deakins’ own account of Sicily says the men landed on a strip “strewn with large boulders and rocks”, under “quite a low cliff”. They then moved forwards in order to scale it, finding it “not much of an obstacle” and a “seemingly easy” climb. This is plausible, and presumably if Deakins had climbed a vertical cliff he would have remembered it, despite the passage of so many years. Clearly, Deakins’ account undermines Harrison’s account, if Deakins was with him.

Not So Formidable Cliffs?

There are other accounts of the cliffs not being formidable. Lt Johnny Wiseman, of 1 Troop, makes nothing of them, saying only “we had the cliffs to climb, we got up the cliffs” (although in another version of his story he mentions in an equally passing manner that scaling ladders were used). Gavin Mortimer, in his book (see below), quotes two men from 3 Troop saying the cliffs were “easy” (though that may apply to a different part of the cliffs, as 3 Troop’s objective was different from 2 Troop’s). Stewart McClean, in his book (see below), says Private Jack Nixon of 3 Troop reported no climbing at all, as there were steps cut into the rock by the Italians.

More tellingly, Mortimer quotes Bob McDougall, who he says was in Harrison’s section. Once ashore, a mate of McDougall’s apparently encouraged him to follow him along the shore, where they found “a path that led from the beach to the top”. Officers did not usually approve of their men wandering off on their own, but if this is in fact correct, and there was a path nearby, why would Harrison have then led the rest of his men up a vertical cliff ?

Harrison says that at first he assumed that his landing spot was the correct one, only later discovering that he was in the wrong place. Lt Peter Davis, like Harrison a section leader in 2 Troop, says much the same, although he differs regarding the severity of the cliffs. In his book “SAS Men in the Making”, written shortly after the war, but not published until 2015, Davis records:

“After assembling on the beach we made towards the cliffs which rose up just ahead. Not that there were really any cliffs, as such, for except for a sharp climb out of the boats of about 5 feet, the shore rose gradually ahead of us in a series of rocky steps and boulders, so the ropes were found to be unnecessary and we were able to reach the top without any undue exertion.”

Further on he explains he later realised he was in the wrong place for the assault:

“We must have touched down half a mile further to the east than planned, with the result that we must now be immediately below the battery […] we had inadvertently landed on the spot which we unanimously agreed from our study of the photos, would be most likely the centre of the danger area.”

This area below the battery is roughly where a map in Harrison’s book shows he landed, although on the eastern edge of it. Davis’s account confirms that this area was indeed not the planned landing area, which he says was in fact about half a mile further west. So where did Davis and his men come ashore, and where exactly should they have come ashore? Two recently discovered documents have the answers.

New Documents

The first document, a British war diary, records two 6-figure map references for actual landing spots. War diaries are not infallible, but, even if correct, these give us locations 100 metres wide, no more, no less, and so are unlikely to map exactly onto the width of the actual positions. We are told that 1 and 2 Troops, the assault troops, landed south-west of the battery, while the mortar troop and 3 Troop landed about half a mile further west, in the area Davis says was the correct one.

No mention is made of a rogue landing craft (i.e. Harrison’s) landing just south-east of the battery. Further east still, the men of a ditched glider had swum ashore and were sheltering in the cliffs [story]. They made no mention of seeing or encountering the SAS, so it seems Harrison’s claimed landing spot indeed remains the furthest east.

The fact that Harrison’s men and Davis’ men did not encounter each other while landing does not necessarily mean that they landed in very different places. Harrison’s boat may have landed in roughly the same place, but later, because it had stopped to rescue some glider men from the sea, while Davis’ boat had not.

The other document is an aerial photograph of Cape Murro di Porco and the coast to the west of it. It was apparently used in the planning process, as it has score marks in its surface showing where tracing paper was placed on it and then inscribed with arrows. Apart from showing the planned landing spots, it reveals the spread of the units along the intended landing area, and shows their roles in the attack.

3 Troop was the most westerly, and an arrow shows it heading north to block the road and seize a farm called Masseria Damerio. Next on 3 Troop’s right (i.e. east), the mortar troop was supposed to land and take up positions not far inland, at the crest of the ridge. Next came 2 Troop, with an arrow showing it was to circle the battery and take up positions to attack it from the north. Finally, 1 Troop was to head straight for the battery, to attack it from the west, starting with a farm adjacent to the battery’s barracks buildings.

On the night, the mistaken landings south of the battery by 2 Troop, as described by Harrison and Davis, put them in danger not just from the fire of the Italian defenders, but also from their own side. According to the plan, 1 Troop was expecting 2 Troop to be on its left, to the north, with only Italians on its right, to the south. Harrison, who had landed in the south, describes making a huge detour to get back on track. Davis says he waited for some time to hear from his CO, and to join up with the other two sections in 2 Troop, before giving up and heading straight for the battery. Both men describe confusion, and coming under fire from British guns.

Harrison’s and Davis’ accounts, as so often with eye-witness testimony, do not tally. Harrison describes the three sections of 2 Troop eventually joining up, before attacking the guns. Davis, on the other hand, says that they did not succeed in finding each other. He adds that 1 Troop was supposed to secure the battery buildings (which tallies with the aerial photo), while 2 Troop was supposed to take the guns, but, in the confusion, 1 Troop also attacked the guns.

Planned and Actual

The idea of landing half a mile west of the battery was probably based on several considerations. The cliffs there were lower, or further inland. The area was sheltered from the battery’s guns. It was far enough away for the battery’s sentries not to hear anything. There was space to assemble and regroup if the landings were chaotic. It allowed the only road leading to the battery to be cut before the assault went in. This would prevent Italian reinforcements attacking the SAS in the rear while they faced the battery’s defenders. As things turned out, however, although 1 and 2 Troops mistakenly landed much closer to the battery, the mistake made no difference to the result.

The map references indicate that 3 Troop and the mortar troop landed in roughly the correct place. We have some corroborating evidence for this. Captain Alex Muirhead was CO of the SRS’s mortars. He recorded in a notebook the number of rounds that his mortars fired, and at what ranges. He noted that the opening salvos against the battery were fired at a range of 750 to 800 yards, which tallies with the plan.

So we can be fairly confident that about half of the SRS landed south of Masseria Damerio, as intended. (The view in this link, looking east from high ground, shows the planned beaches below on the right. At the top of the ridge on the left, the roof of a small building shows roughly where the SAS mortars were to be positioned.)

We can also be fairly confident that the rest of the SRS mistakenly landed south-west of the battery, where the rocky shore comes gradually down to sea level, and the cliffs recede inland in steps.

As to whether Harrison’s men climbed vertical cliffs without ropes, it’s unclear. He does not exactly say that they did, although it’s easy for a reader to infer it. He admitted to having a fear of heights, which would exaggerate the risks for him. And if you lose your grip while climbing a steep bluff, you can tumble to your death as surely as from a vertical cliff. It seems very unlikely that he led his men up a vertical cliff – but who knows? Just because a story is dramatic and glamorously heroic, it does not necessarily mean it is not true.

Other stories and photographs of the cliffs of Cape Murro di Porco can be found here and here.

Thanks to Paul Davis for permission to quote from Peter Davis’ book and to use a photo from his album.

Thanks also to the Muirhead family for allowing me to see Alex Muirhead’s documents and photographs.

Books:

Peter Davis, “SAS Men in the Making” can be bought from the publisher here.

Gavin Mortimer, “Stirling’s Men” can be bought from the publisher here.

Stewart McClean, “SAS – The History of the Special Raiding Squadron – Paddy’s Men”, can be bought via the publisher here.

D I Harrison’s “These Men are Dangerous” and W A Deakins’ “The Lame One” both seem to be out of print.

My father, William Gears told me that he was in the party sent in to Sicily with the raiding party. He was very sick into cardboard buckets before he got ashore. I was always doubtful of this until I read reports years later. He was very secretive about his experiences except when ‘World at War’ was on TV showing the guns at the start of the battle at El Alemein in the dark when he told me he was 200 yards in front of the guns lifting mines with his bayonet. He was at Dunkirk (taken off but put back ashore at LeHarvre to leave France later. He was one of the first on the beaches on D Day but was injured on a hill near Arromanches. He said he knew nothing but awoke in Dundee several days later.

Thanks for that, Alan