Waco glider 57 landed in the sea off Sicily, near the forbidding cliffs of Cape Murro di Porco. As the men floundered onto the wing, they came under fire.

Glider: CG-4A Waco 57

Glider carrying: CO and men of Battalion HQ of 1 Border Regiment.

Troops’ objective: Outskirts of Syracuse. For more detail, see here.

Manifest

CO

Batman

Adjt

RSO, 18 set

1 man Def Sec

2 Sigs, 18 set

2 Sigs, 68 set

MO

I Sjt

1 man I Sec

Handcart

5 or 6 folding bicycles

Names:

Lt Col G V Britten, Bn CO

Capt G G Black, RMO

Lt J S D Hardy, RSO

Capt N A H Stafford, Adjutant

Sgm Gilbert

Sjt Burton

Cpl Day

L Cpl Smith

L Cpl Toman

Pte Clark

Pte Cull

Pte Ditte

The men in Waco glider 57 represented half of the Battalion HQ of 1 Border. Apart from the commander and his immediate team, it included a small intelligence unit and four signallers under the battalion’s Regimental Signals Officer, Lt Hardy [account]. The signallers carried two 18 Set radios [info] for communicating with the battalion’s companies. They also carried a 68 Set radio [info] for communicating with the battalion’s parent formation, 1 Air Landing Brigade (1 ALB). Both radios were in theory man-portable, but were heavy and would benefit from being carried in the handcart [info]. In the absence of vehicles, the HQ men could move about the battlefield on bicycles [info], and couriers could substitute for radios. All this equipment was lost when the glider landed in the sea.

The other half of the HQ, headed by the battalion’s second in command, with duplicate equipment, was carried in glider 58. Glider 58, however, like glider 57 and many others [story], also landed in the sea. This meant that there was no battalion HQ in action during Operation Ladbroke, and, without radios, no information at all reached 1 ALB or 1 Airborne Division about the progress of the glider troops. Command on land fell to Major Du Boulay as the next most senior Border officer, even though he had been wounded.

It was not just the battalion HQ that failed to land entirely, or almost entirely. The battalion’s Regimental Medical Officer, Captain Black of 181 Field Ambulance (181 FA), was out of action with the rest of the men from glider 57, but so also were all the 181 FA gliders assigned to land with the Border troops. These were gliders 62, 66 and 70, all of which carried only medical men [story]. All three gliders landed in the sea. Luckily, a few other medics had been scattered among the gliders of the Border fighting troops, and these provided vital aid to the wounded.

After-action reports stressed the lesson learned here: disperse important equipment and personnel among multiple gliders.

USAAF Tug Pilot’s Report

Tug: C-47, 41-18446, 7 Squadron, 62 Troop Carrier Group, 51 Troop Carrier Wing USAAF.

Takeoff: 19:15, from Airstrip C, El Djem No. 2, Tunisia. Priority 1.

Tugs returned: Between 00:38 and 04:15, except one landed at Sfax.

Pilot: 2nd Lt. John A Hartley

The pilots of 62 TCG must have submitted individual reports at debriefing, but if these were recorded, the document does not seem to have survived. A group report stated:

“Gliders released 2 – 5 minutes late owing to excessive wind. 4 gliders reported released early, but pilots consider they should have reached L.Z.”

Glider Pilots’ Reports

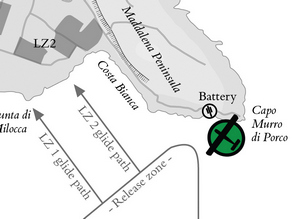

Glider allotted Landing Zone: LZ 2.

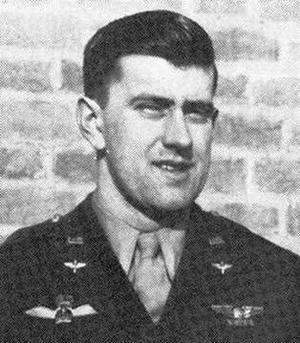

First pilot: Lt William R Buchan, British Glider Pilot Regiment (GPR).

Second pilot: F/O Paul O Rau, US Army Air Force (USAAF).

Left: Lt William Buchan in a 3rd Squadron photograph taken in Putignano in Italy in November 1943. Source: Buchan. Right: American F/O Paul Rau in a photograph taken some time after Operation Ladbroke. The wings on the right breast of his jacket have a crown at the centre, so cannot be American. They are in fact British GPR wings, awarded after the operation to the US GP volunteers who flew to Sicily as co-pilots. Source: US NWWIIGPA.

The divisional report is apparently based on Lt Buchan’s debriefing, as he was first pilot:

“Glider pilot stated tug a/c made incorrect approach – not as planned. Intercomn went u/s. Glider cast off at 2250 hrs, at 1400 ft, approx. 2½ miles off shore; could not make land and came down in sea approx ¼ mile off CAPE MURRO DI PORCO.”

Flight Officer Rau, an American glider pilot volunteer flying in the second pilot’s seat, reported:

“Just west of Cape Murro di Porco, I was in doubt as to our exact position because we seemed to have changed heading a few times. Finally we recognized the spot we were supposed to go in over and we cut loose and made a turn toward shore. A few minutes before peeling off the searchlights appeared and the flak was fairly heavy. The number of lights and the amount of flak seemed to increase as we cut toward shore.

As soon as we started our glide in we were almost sure we wouldn’t make land. At 500 feet we warned our troops to get ready for a ducking. We hit shortly afterward and the fuselage immediately filled with water.”

A further report is available in Lt Hardy’s account. He was a passenger and, as one of the officers on board, was probably seated not far behind the pilots:

“There was a little flak, but none of it came very near us at all. Our pilot cast off at what we, the crew, thought was the correct place, but which was as near as the tug was willing to go without taking evasive action. We were actually quite a way out at a height of only 1300 ft. We glided all along the South coast of the Cap du Porco, heading straight for the LZ, but could not make landfall. Lt [Buchan] gave us “prepare to ditch”, but his order was not heard at the back of the glider. The front emergency doors were jettisoned, and the rear doors still locked when the glider actually hit the water.”

As so often with multiple witnesses, these accounts do not quite tally, nor make sense in every respect. For example, Hardy and Rau disagree about the amount of flak (which was probably mainly coming from the battery near the tip of the cape). More significantly, it’s hard to see from their accounts how glider 57 ended up where it did. If it was released west of the cape (as Rau implies), and turned towards LZ 2, it would have been heading north-west, yet we know it ended up at the eastern end of the cape. Equally, if it travelled all along the south coast of the peninsula (as Hardy says) from east to west, again it makes no sense that it ditched where it did.

Two of the three accounts at least agree that the tug pilot seemed lost or off course, although Hardy’s suggestion that the tug refused to go closer to avoid flak must be supposition, as the intercom had failed and the tug pilot could not have explained this. It is not implausible, however, as we know the tugs had been ordered to keep their distance for exactly this reason [story]. Buchan’s estimate that the glider was released some 2.5 miles out is the best explanation, as it was nearly 50% further out than the intended 1.7 miles. Distance from the shore was almost impossible to gauge for both the glider and the tug [story].

Glider 57 in the Sea

All 14 men in the glider (including the two glider pilots) managed to escape from the water-filled glider and clamber onto the wings, which remained level with the surface. Several gliders floated nearby, some further out in the bay, some nearer the cliffs. Among them was glider 2, piloted by Lt Col George Chatterton, the CO of the Glider Pilot Regiment, which carried Brigadier Philip Hicks, the CO of 1 Air Landing Brigade. Lt Col McCardie, CO of 2 South Staffords, was also in the sea not far away, clinging onto glider 3. Along with Britten, CO of 1 Border, who was in 57, this meant that no less than four out of the operation’s top five commanding officers were “in the drink” together near the cape that night.

Fairly quickly they came under fire from machine guns on the top of the cliffs. A battery of three large anti-ship guns was located on the cliffs, not far from the lighthouse at the tip of the cape. Named “Lamba Doria” after an Italian naval hero, the battery was equipped with searchlights and surrounded by barbed wire. Its defences included machine guns against ground attack and 20mm AA cannons against air attack. It was these that had poured AA fire at the gliders as they approached, hitting Chatterton’s glider as he banked it steeply to avoid crashing into the cliff face.

The Italian machine gunners kept firing at the downed gliders. They sent up one flare after another to light up their targets. Luckily, it seems that the machine guns could not depress quite enough to hit the gliders, and the bullets whizzed over the heads of the troops cowering on the wings. Nobody was hit.

Nevertheless it was not a predicament that Britten and the men on glider 57 wanted to continue. They agreed to swim for shore, to try to silence the machine guns. This was a bold plan, as they only had a few revolvers between them. They decided to swim in small groups to avoid attracting attention and alerting the enemy. It seems the combatant officers (Britten, Buchan, Hardy and Stafford) went first, presumably as they carried the pistols. Black, the Medical Officer, was a non-combatant [but see the story of glider 26]. Later, half a dozen or so of the remaining men set off from the glider, presumably led by Black and the two sergeants. Three or four men, including US co-pilot Rau, stayed on the glider, as they either could not swim at all, or not well enough to battle the current.

When the officers reached the cliffs, they found them unclimbable in the dark, and they decided to shelter in a cave until daylight. After a while, Buchan swam out to find the rest of the men, but he could not find the glider. He swam back to the cave.

At 2:15am several squadrons of British Wellington bombers attacked Syracuse in support of the glider troops. A bomber, possibly from this group, was hit by AA fire, perhaps from Lamba Doria, while it was approaching the cape. The plane jettisoned its load near the cliffs and then crashed into the water only yards away from the glider men. Stafford was injured, but it seems none of the other men sheltering in the cliffs or floating on the gliders was hurt. The plane sank, leaving a large slick of aviation fuel burning blue on the surface of the swell (the wreck of what is possibly this aircraft was recently discovered 100 yards off the cape). Rau saw parachutes and assumed it was the crew descending.

The Arrival of the SAS

Not long afterwards Rau and the men still clinging to glider 57 watched the troopers of Britain’s elite SAS Special Raiding Squadron (SRS) attack and destroy the Lamba Doria battery. The scene was also witnessed from afar by the commanding admiral of the invasion fleet, who described how it seemed that the SAS “carried fire and the sword” to the Italian defences. The SAS had arrived by landing craft further west along the cape [story], where they had discovered Chatterton, Hicks and the others from glider 2, who had swum ashore and were sheltering in the cliffs. Glider 2’s men joined the SAS and climbed to the top.

Apparently none of the other men from glider 57 saw the SAS arrive in the dark, probably because they were too far east and tucked under the cliffs. When dawn came, however, they had a ringside seat for a magnificent view of the invasion fleet to the south, where ships and landing craft thronged the waters off George Beach, near Cassibile. Rau remembered:

“It was a wonderful sight, all those boats.”

As planned, the officers from glider 57 now attempted to climb the cliffs. Buchan recorded in his diary:

“0700 we join up with seven others of the crew in another cave. 3 are still on glider: it drifts to shore near the point and they go ashore. We salvage food and 2 .38 pistols from two other gliders which drift past under our cave.”

Rau, one of those still on the glider, recorded:

“The tide was coming in and we started drifting toward the peninsula. We helped along by paddling with whatever we could use and finally got ashore. We were afloat for 12 hours. We climbed to the top of the peninsula. It was very steep and rocky and it took us some time as we had no shoes.”

About the same time Britten decided that he should try and reach the rest of the battalion some miles away near the Ponte Grande bridge. Hardy says the decision was taken at 10am, and that he and Britten set off at 2pm. Buchan says they set off at 5pm. It’s not explained why several hours passed between the decision and the action, nor why the rest of the men were left in the cave. Presumably they were ordered to stay there by Britten.

The Maddalena

Britten and Hardy now made their way north-westwards through the Maddalena Peninsula, much as Rau and the other non-swimmers were doing. Both groups were moving in the wake of the SAS, who had long since stormed along the spine of the peninsula, overcoming defended farms and gun batteries one after the other as they went.

Italian resistance had collapsed. Both sets of airborne wanderers had various adventures (see Hardy’s account), encountering groups of Italians who were already prisoners, or who they disarmed, or who lay wounded in the farms. They took advantage of the situation to get water, eat, arm themselves and even make tea. By now the battle for the Ponte Grande bridge was over. Meanwhile those left in the cave spent the day watching the drama of Axis aircraft attacking the fleet, dog fights as Allied fighters defended, and naval shelling of Italian strongpoints and batteries.

Britten and Hardy finally made contact with Battalion HQ at about 9pm, just as British seaborne troops were capturing Syracuse. Rau and his companions spent the night at an Italian farm, lying on straw provided by the farmer. Next morning they met a British medical officer leading a donkey cart. They rode to rest their sore feet until they reached the main Syracuse highway. They then walked the rest of the way, and had the satisfaction of crossing the intact Ponte Grande bridge, which meant their mission had been a success. Meanwhile Hardy had returned to the cave and gathered the rest of the men.

Aftermath

Operation Ladbroke was the first major operation for Britain’s glider pilots, and they endured the aftermath of most first actions: the sad shock of finding men missing in the mess, who had been firm friends though months and years of training. Buchan recorded many names of the dead. He also expressed the resentment many glider pilots felt towards the tug pilots. Next to a clipping of an upbeat newspaper article by a journalist who had flown on Operation Ladbroke in a tug plane, Buchan wrote what had happened to the glider pilots towed by that plane. Both had broken their legs in a crash landing, leading in the co-pilot’s case to amputation.

The survivors also felt the relief that survival brings, and the preciousness of living. Later, after an evening of food, whisky and music back in camp in Tunisia, Buchan wrote simply:

“Life is good”.

Rau ended his report with a not dissimilar observation:

“It was an experience I shall never forget. And now that it is over I’m glad to have been part of it.”

For other in-depth stories about individual gliders in Operation Ladbroke, click here.

Photograph of Paul Rau courtesy of the US NWWIIGPA.

With thanks to Ian Buchan for photos of his father and family documents.