Your correspondent dropped behind the lines on the weekend of D-Day 2004 to send back an eyewitness despatch from the struggle to organise and celebrate the anniversary of the greatest airborne operation in history.

NORMANDY, 4-7 JUNE 2004. 60 years after the invasion of German occupied Europe by British, American, Canadian, Polish and French forces, hundreds of thousands of veterans, visitors and VIPs from these nations, as well as from liberated countries like Holland, reinvaded a heavily defended Normandy last weekend.

Officially, they came to commemorate and honour the sacrifice of those who fought and gave their lives so that we might be free today. Unofficially, they also came out of duty, out of curiosity, to search for memories, to find meaning, to play at being soldiers, to sell mementoes, to meet heroes, to catch at the hem of fading glory, or simply to party.

“It was something we had to do,” said a British officer on the windswept top deck of the ferry Normandie, as it followed in the ghostly wake of long-scrapped Allied assault ships and approached the mouth of the river Orne at Ouistreham, on the easternmost edge of the invasion zone.

The officer was referring to the crusade against Hitler. “The issues were clearer then,” he explained, alluding by contrast to ideologically messy conflicts like today’s “crusade against evil” in Iraq.

Below decks, actor and veteran Richard Todd was surrounded by colleagues and fans. Todd starred in Darryl F Zanuck’s star-studded 1962 D-Day epic, “The Longest Day”. He played Major John Howard, commander of the glider force that seized the bridge over the Orne canal, now known as Pegasus Bridge, an operation in which Todd himself fought.

Around him 80-year-old British veterans in berets and blazers loaded with medals gloried in their momentary celebrity status. They shook proffered hands, signed autographs, had their pictures taken with fans, or flirted cheekily with 50-year-old girls. The disparity with the normal treatment we accord our elderly was poignant.

Pegasus Bridge, Benouville

Near midnight on Friday at Benouville, the site of Pegasus Bridge, French volunteers were still frantically assembling and painting a replica Horsa glider for an inauguration ceremony the next day. With Prince Charles as guest of honour, security was tight, and the volunteers were under orders to leave promptly. Helicopters patrolling with searchlights and armed anti-terrorist troops on motorcycles ensured that they did not forget.

It was at this time of night, on the night of 5 – 6 June 1944, that Major Howard’s tiny force from the British 6 Airborne Division landed next to the bridge in Horsa gliders. Many years later, still indomitable, Howard led a tiny force of elderly residents against state nannyism in his old people’s home. Making a stand against being treated like a child during a government anti-salmonella drive, he protested: “If I was old enough then to face the risks of dropping behind enemy lines, then I’m old enough now to face the risks of eating a boiled egg.”

Howard’s mission in the short hours of darkness before D-Day was to take the Orne canal bridge by coup de main, and then hold it against German counter-attacks on the flanks of the beachhead. The assault was successful, and a cafe next to the bridge owned by M. and Mme. Gondree became the first house to be liberated on D-Day.

Six decades later, the party outside the Cafe Gondree went on until dawn. Groups of modern paratroopers, re-enactors, WW2 vehicle collectors and military fans sang raucous songs, including some from the wrong world war, like “Inky, Pinky, Parlez-Vous?” A young drunk shouted at passers-by approaching the bridge: “That’s right, you cross it, we took it.”

A veteran claimed to have talked to the piper of Lord Lovat’s commandos, the seaborne force which relieved Howard’s men on D-Day. He said the piper told him that he had not, as reported, played his bagpipes while the commandos marched onto the bridge under fire. A plaque on the wall of the cafe’s car park implies otherwise. The myths of D-Day are inescapably full of such misty-eyed Darryl F Zanuck moments.

On Sunday 6 June 2004, a cordon sanitaire descended on the bulk of the Norman coastline, from Sword Beach in the East, to “Bloody Omaha” in the West, to keep back the hordes of tourists and terrorists expected to logjam the roads. Bayeux and Arromanches themselves became doubly defended super-citadels within this zone, to protect visiting premiers like Bush and Chirac. Ironically, their relationship as allies is as frosty today as that between Roosevelt and De Gaulle was all those years ago.

St Mere Eglise

On the extreme western edge of the invasion zone the town of Sainte Mere Eglise was also locked down, and almost as hard to get into as 60 years before. It was around this town that US airborne troops landed to take the bridges over the Merderet river, in an operation whose goals exactly mirrored those of their British counterparts on the Orne to the East.

In honour of another (real-life) Darryl F Zanuck moment, the full-size effigy of a paratrooper, whose parachute caught that night on the spire of the church, hung in his harness above the vast sound system in the town square.

Every thronging street was wreathed with smoke, not from fires started by high explosives, but from barbecues every 100 paces. Consumed with armfuls of fresh baguettes the size of bazookas, more Merguez and Toulouse sausages were fired on grills this weekend than similarly sized .50 calibre rounds were fired that midnight long ago.

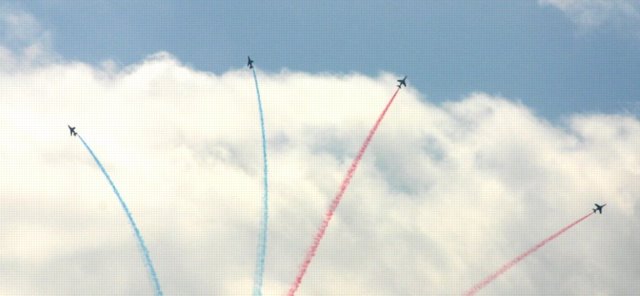

In perfect summer weather, the kind that people remember for decades, 50,000 visitors yomped like paratroopers the hot two miles from the town to the drop zones, to watch 600 soldiers parachute from wave after wave of transport aircraft, some of them jet-powered giants shaped like Thunderbird 2. Then the crowds yomped back again for hours of music in the square, fireworks, and yet more sausages.

After two exhausting and dehydrating days, the veterans, some of whom had been on the go since the end of May, were wilting, as were the visitors and French officials. There was another official ceremony on Sunday evening at the site of Sainte Mere Eglise’s Cemetery Number One (there were so many dead then that the temporary graveyards needed numbering). Immediately recognisable by their white hot-dog vendor look-alike caps, it was obvious that embarrassingly few US veterans occupied the seats reserved for them.

The wife of the commander of a modern parachute unit consoled a veteran whose own wife was too afflicted by arthritis to come: “There’ll be another. There sure is enough of them to go round, these ceremonies.” With unintended irony, passing in the street, a member of one official choir called out to a member of another: “Is this your last ceremony?”

Too many ceremonies, too few veterans. An elegiac sense of finality and loss pervaded all the exhibitions, junketings, memorial services and wreath layings. Everybody, especially the old soldiers themselves, knew that there may be hardly any veterans still present at the next decennial.

Despite the overload of heat, well-meant gratitude, parties, ceremonies, services and sausages, there was one emotion, however unbearable, whose surfeit was borne by all regardless: sorrow. Although evident everywhere, this common humanity shone brightest, not in the official, mass events, but in small, intimate memorial ceremonies shared by veterans and French locals. Many were held at the dozens of crossless calvaries that dot the villages, water meadows and hedge-lined lanes of the Cotentin bocage.

Chef du Pont

Private Bill Tucker jumped that distant night with the 505 Regiment of the US 82 Airborne Division. On Saturday morning he witnessed the unveiling of a new stone near Fresville which marked the spot where seven of his fellow paratroopers fell to a single machine gun burst. “After all these years, it’s good that it’s closed out, “ he said. “Now we won’t need to lay roses every year just to mark the place. Now other people can remember for us.”

Corporal Harry Hudec, attending a ceremony by the bridge at Chef du Pont, jumped with the 508. Although surrounded by veterans and their wives, he seemed alone, as if somewhere far away. He dried his eyes constantly during the long wait for the ceremony to begin. Still a great bear of a man, although bowed at 82, he approached the impossibly young officers of the colour party of the honour guard of the modern 508th, to exchange a few comforting words of bluff and masculine banter, his voice gruff with age.

He sat restlessly amongst the places of honour again, again with his handkerchief in his hand, dabbing repeatedly, remembering the lost, never to be refound camaraderie of the young men with whom he faced death, who found death in this place.

Apparently readier to jump into flak-filled darkness than endure this haunted waiting any longer, he finally called out, as perhaps he did that fear-filled night so long ago, “Come on, let’s go, let’s get this thing done!” In so doing, he spoke the words that a whole, now passing generation did, when they were young.

Although events continued on Monday, all over Normandy the red, white and blue flowers of the wreaths, as yet unwilted, lay unremarked at the foot of wayside memorial stones deep in the empty countryside. There was utter stillness in the great heat. Finches sang, the elder flower and the rambling rose reclaimed the hedgerows.

Links

Memorials at Chef du Pont